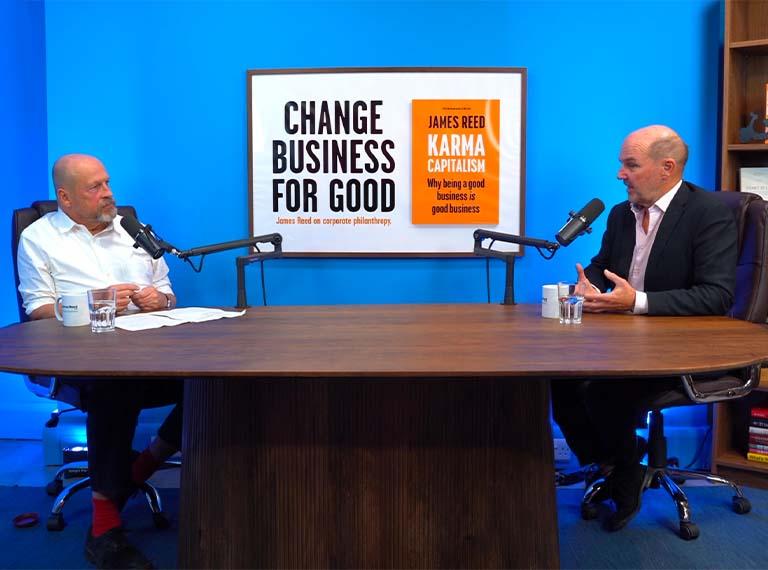

Watch the episode

Listen to the episode

Television is something we all enjoy. But few of us get to see how the shows we love actually come to life and why some of them grip the nation in what can only be described as a phenomenon.

In the latest episode of all about business, James Reed is joined by Stephen Lambert OBE. Stephen is a producer and founder of Studio Lambert, the production company behind some of the UK’s most successful shows like The Traitors, Gogglebox, Squid Game: The Challenge and Race Across the World.

Stephen explains how he built the UK’s most successful independent production company, what goes into producing formats that connect with audiences around the world, and why encouraging risk-taking and innovation is so important in TV.

James: [00:00:00] Welcome to All About Business with me, James Reed, the podcast that covers [00:00:05] everything about business management and leadership. Every episode I sit down with [00:00:10] different guests of bootstrap companies, masterminded investment models, or built a [00:00:15] business empire. They're leaders in their field and they're here to give you top insights and [00:00:20] actionable advice so that you can apply their ideas to your own career or business.

[00:00:25] Venture television is something we all enjoy, [00:00:30] but few of us get to see how the shows we love actually come to life. My guest today is [00:00:35] Steven Lambert, founder of Studio Lambert, the production company behind shows like the [00:00:40] Traders, Gogglebox and Squid game, the Challenge. We'll be talking about how he's [00:00:45] built a creative and successful independent production company.

What goes into [00:00:50] making formats that connect with audiences around the world and why encouraging risk taking and [00:00:55] innovation is so important in tv. Well today on all About [00:01:00] Business, I'm delighted to welcome Stephen Lambert to our studio. Stephen is [00:01:05] the Chief executive of Studio Lambert. Now, you might not have heard of Studio [00:01:10] Lambert, but I'm sure you'll have heard of Studio Lambert's Output.

This is a, a big time of [00:01:15] year because, uh, Stephen and his team produce the TV series Traitors, [00:01:20] which is topping the polls. They also produce Goggle Box and, um, race Across the [00:01:25] World, which is coming soon. Celebrity Race across the World and a lot of other shows [00:01:30] including Squid Game, the Challenge. So Traitors and Race Across the [00:01:35] World are the top performing shows on the BBC, I believe Steven and Squid Game.

[00:01:40] The Challenge was a top performing show on Netflix at one point, and you've recently [00:01:45] returned from, uh, Los Angeles with an Emmy and been awarded an OBE by [00:01:50] the King. So this has been a pretty busy period and I'm really looking forward to talking to you about. [00:01:55] How all this came to pass and how you do it.

But should we begin at the beginning, Steven? I mean, you [00:02:00] were a, the, the premier TV producer in Britain at the moment, but how [00:02:05] did you start out and how did it begin?

Stephen: Thank you, James. It's a pleasure to be here. [00:02:10] Well, when I was at university, I thought I probably wanted to work in television. Um, but I didn't really [00:02:15] know how to get into television.

So I was given a grant to start a [00:02:20] PhD at Oxford, at Nuffield College. And I thought, well, that's good. I'll, I'll, I'll [00:02:25] write about television as my PhD subject. And when I was [00:02:30] there, they said, oh, you should talk to this man, Anthony Smith. He was, he [00:02:35] had been at Oxford, but he was then running the British Film Institute.

And I went to see Anthony and he [00:02:40] said, oh, you're just the person we're looking for. We're looking for somebody to write a book about how Channel [00:02:45] four came about. It's about to launch, uh, it's gonna launch in about 18 [00:02:50] months. Could you write it quickly? And then it could come out on the day of the launch of the channel.

[00:02:55] This was in November, 1982, and the, you might think, why would you write a [00:03:00] book about a channel that hasn't started? Yeah, I'm thinking

James: that Stephen. So, yeah, go on. [00:03:05] So why, what, what was going on there? Well, 'cause

Stephen: really it was a history about the ideas of British broadcasting, [00:03:10] British broadcasting policy.

Because when, when radio began, the, [00:03:15] the, the, the government at the time looked, had an inquiry in the twenties, and they [00:03:20] looked at American television, ra, American radio. Of course it wasn't television at this point. Yeah. They looked at [00:03:25] American radio and they said, oh, we don't want that. It's highly competitive.

It [00:03:30] seems very, very. Tacky. And so they said, so

James: competitive and tacky. So un [00:03:35] British, statistically Ack. Oh, okay. Yeah. And they

Stephen: found this, this wonderful man, John Reath, [00:03:40]

James: right.

Stephen: And they decided, no, we're not gonna do that. We're going to have the BBC. [00:03:45] And the BBC would. Inform, entertain, [00:03:50] um, and, and, and, and, and educate.

In fact, the entertainment bit was [00:03:55] always as regarded as sort of an un an unfortunate necessity, [00:04:00]

James: right?

Stephen: Even in the sixties, that was at the

James: tacky end. That was tacky

Stephen: end. Even in the [00:04:05] sixties, light entertainment was referred to as ground bait. Oh. It would be something you'd scatter [00:04:10] out there to get people to start watching or listening, and then they would ground bait, maybe [00:04:15] Ground bait, like in when you go fishing.

Right. Okay. Anyway, I didn't know that. So that [00:04:20] was, um, the BB, C and then after the war, there was a whole campaign, 'cause obviously television [00:04:25] had launched just before the war, and then it started up again after the war, but it was just one [00:04:30] television station on, on the B, B, C and then. There was a whole campaign, no, [00:04:35] we need to have competition.

And the conservative governments in the, in the, in the 1950s [00:04:40] bought into that idea and they launched ITV. But at that point, if you wanted to have a [00:04:45] good signal across the country, you could only have two channels. Then in the sixties [00:04:50] they had an a sort of upgrade in the sort of technology, and they were [00:04:55] able to have four channels.

And everybody thought those two extra channels would be [00:05:00] competitive to ITV and BBC, that there'd be more competition. 'cause that was the sort of idea that had [00:05:05] come into, into play in the fifties. But actually [00:05:10] again, things didn't work out that way. People argued [00:05:15] no competition leads to a kind of chase to the bottom.

And the BBC argued [00:05:20] for a complimentary channel, a channel that would do the opposite of what everybody else was [00:05:25] doing. And they managed to get BBC two as this complimentary channel. So when

James: did that happen? [00:05:30] BBC two. That happened

Stephen: in 64, right? David Attenborough was the first channel controller. [00:05:35] And then everybody thought, well, what about the fourth channel?

And they didn't quite know [00:05:40] what to do with the fourth channel. There was an idea that it would be a competitive channel to the others, [00:05:45] but then people thought maybe not. And then. In the end, the [00:05:50] authority for independent television said, no. Maybe it should be also complimentary [00:05:55] for, so ITV should have it.

And just as that was about to happen in the [00:06:00] seventies, there was, um, an argument put out and [00:06:05] it gained traction. It said one of the problems with television is that all the programs are [00:06:10] being made within the institutions. Either they're all made within the B, B, C [00:06:15] or they're all made within ITV. It is a very funny idea.

I mean, if you look at [00:06:20] publishing, they argued you don't have authors employed by publishers. [00:06:25] Publishers are able to pick and choose and they that they take [00:06:30] the best talent for that moment rather than having everybody on [00:06:35] staff. And so the idea of independent television was, uh, independent [00:06:40] production was created, and this argument won the day eventually, so that [00:06:45] by the early eighties or in fact the late seventies, the Thatcher [00:06:50] government had come in and they were convinced.

Everybody thought that this idea of independent [00:06:55] television and Channel four would be one that she wouldn't like, but she did because she [00:07:00] was sold on the entrepreneurial argument. This would create small businesses that [00:07:05] would thrive and would challenge the kind of, uh, sort of orthodoxy of, [00:07:10] of, of everybody being employed by either the BBC or by ITV.

And [00:07:15] that's how independent television production came about. And the person who was running [00:07:20] Channel four at the time, a man called Jeremy Isaacs really championed that because [00:07:25] although ITV, the ITV companies made quite a few of the programs were Channel four when it launched, he [00:07:30] was determined that no, the independents.

Played the biggest role, and [00:07:35] it was so successful and the independent productions programs [00:07:40] were so well regarded and the argument that this entrepreneurial sort of spirit should [00:07:45] be encouraged that a few years later the government required the [00:07:50] BBC and ITV to take a minimum of 25% of their programs have [00:07:55] independent producers.

And this really started to lead to the growth of [00:08:00] independent production. And then it was dramatically accelerated in the [00:08:05] early two thousands when we all campaigned the government and said. Look, [00:08:10] it's great that we exist, but we've really only got these few buyers, [00:08:15] I-T-V-B-B-C, and channel four, and we're in a kind of surf like relationship with them.

They take [00:08:20] all the rights. They, they don't give us much money to make the programs [00:08:25] as, as a sector. Were not able to, to, to make much of a profit. And so [00:08:30] nobody's actually investing in our sector. And there was a change to what's called the terms of [00:08:35] trade. And these change, these changes led to the fact that the independence would then keep [00:08:40] their, the rights to their programs.

They would be able to exploit them and sell the tape, the Finn [00:08:45] programs or the formats to their shows around the world. And they would be able [00:08:50] to maybe give some of that to the broadcaster. 'cause the majority would stay with the independent producers. [00:08:55] This transformed the bottom lines of independent production.

It went [00:09:00] from an average of like two or 3% to something closer to 10 or [00:09:05] 12%. And it meant that money came into the sector and the, the companies, [00:09:10] the independent production companies became much more muscular and they were able to kind of back [00:09:15] their own ideas and become a proper sector.

James: Well you, I mean the difference between [00:09:20] two or 3% and 10 and 12% is huge, obviously.

And it that. It's barely a viable business at [00:09:25] two or 3%. So I can see, so your original, original research when you were preparing this [00:09:30] book or PhD thesis, sort of was exploring this, it was opening up of the market and [00:09:35] Yes, it was the, so you had an early, early sight of this in a way you could see this coming?

Well, I [00:09:40] was. I

Stephen: was, I was. 'cause I was, I was interested in how those ideas of, of kind of [00:09:45] Monopoly BBC from the twenties and thirties, how that had [00:09:50] evolved into the point where this idea of encouraging entrepreneurial independent [00:09:55] producers came about and it was embodied with the launch of Channel four.

Obviously the [00:10:00] book stopped at that point, but my interest in the subject continued.

James: Yeah. Clearly. Clearly. And, but [00:10:05] you then worked at the BBC didn't you for quite a long period. Tell me about that a little bit, Stephen, [00:10:10] what were you doing there? Well,

Stephen: after, after writing the book, I was able to use it [00:10:15] as a, as a way to get into the BBCA slightly unusual way because I joined the BBC [00:10:20] Secretariat, which is the body that serves the Board of Govern, governors and the board of Management [00:10:25] as a kind of research assistant.

And, but once you're inside the BBC, [00:10:30] it's easier to move. And within three months I got a move to the, [00:10:35] uh, the bit, the documentaries, the television documentaries department where I stayed for the next 16 [00:10:40] years. I mean, it was a very exciting place to be. I ended up becoming a producer, [00:10:45] director of documentaries all around the world, often in war zones.

Uh, and then eventually I became an [00:10:50] executive in charge of commissioning programs. Documentary programs and, um, sort [00:10:55] of,

James: so many, many of our listeners would've seen some of these programs. I'm absolutely sure. I mean, just share two or [00:11:00] three, I mean, some of the most high profile documentaries or stories that you brought to us.

Stephen: Well, I [00:11:05] was doing a mixture of things. I mean, as a filmmaker, I was often in sort of troubled areas [00:11:10] making films about, I don't know, the Tamil Tigers. I was the only person to interview the [00:11:15] Tamil Tiger leader in his hideaway in the. In the, in, in the jungles [00:11:20] of, of Northern Sri Lanka. I would make a film about, I dunno, British mercenaries [00:11:25] who were working with the, the Croatian army during the breakup of [00:11:30] Yugoslavia or the South African police during the time that Mandela had [00:11:35] just been released.

And they were very worried about what was gonna happen to them, the, the, the white South African [00:11:40] policemen. But then as an executive, I looked after a a, a, the [00:11:45] BBC two's main documentary strand. It was called Modern Times. And I also did some of the [00:11:50] first docus soaps that we did a docus soap called Clampers about parking wardens.

And [00:11:55] uh, we did a, we did a real dokey

James: soap, you call it. I like that expression. Docu soaps. [00:12:00] Yeah. They're

Stephen: sort half hour. Yeah. Uh, very popular. Uh, BBC one [00:12:05] documentary shows that sort of started in the sort of early nineties. So

James: [00:12:10] this sounds, I mean this, this sounds like sort of early nascent, what became reality TV is, was [00:12:15] that what you'd say?

Is that what was happening? Yes. I mean,

Stephen: the whole history of observational [00:12:20] documentary and what people call reality TV is, is, is there are two things [00:12:25] that sort of sit side by side and they feed off each other. I mean, they're essentially [00:12:30] both interested in capturing natural dialogue, people [00:12:35] talking to each other in real, in present tense situations.

Yes. Rather than telling a [00:12:40] story after the event and [00:12:45] reality television or what we often now call unscripted 'cause it sort of captures everything. But [00:12:50] reality television came about, but both of [00:12:55] them sort of, Ben benefited enormously from the development of, of, of lightweight cameras. [00:13:00] You know, particularly the 16 millimeter lightweight film camera and the separate [00:13:05] sound recording.

And it enabled you to be incredibly portable in a way that, [00:13:10] you know, for years one wasn't able to be, and reality television [00:13:15] sort of. Properly started, I suppose, in America with, with, with, with the [00:13:20] American family in the early seventies and then onto the, the real world, which was a [00:13:25] big hit on MTV. They were very [00:13:30] similar in many ways to what I'd call observational documentary, which is what we were doing in the [00:13:35] documentaries department at the BBC, but perhaps with a stronger [00:13:40] entertainment sort of imperative, I think.

So the

James: educating form was going [00:13:45] more towards entertainment, definitely, which is a journey that's continued really, and also

Stephen: creating the situation. I think the [00:13:50] big difference between. There's one kind of observational, uh, [00:13:55] uh, television where you are observing things that are happening that would be happening anyway.[00:14:00]

Right. And there is another one where you create a situation, uh, which [00:14:05] is great from a, I'm thinking of

James: Ross Castle at this point. Oh, Ross

Stephen: [00:14:10] Castle. Or, when I first, when I left the BBC after 16 years, I joined a, a, [00:14:15] a, a relatively small, independent production company called RDF. Television [00:14:20] or IDF media and, and suddenly realized we weren't gonna be able to [00:14:25] build a business unless we could create returning programs.

[00:14:30] And because the What do you mean by returning programs? Well, television is sort of made [00:14:35] up a programs that are either they happen and that's it. They can be a single program. You [00:14:40] watch that program that, that, that night. Or they can be like a limited series that, [00:14:45] that they will be three or four, maybe even six episodes.

But that's it. [00:14:50] You, you, you, the, the, the, they're not conceived and they're not designed in such a way that the whole thing [00:14:55] comes back again, right? A year later, or even less than a year later. So this was

James: key in your mind for a [00:15:00] business.

Stephen: You can't run a business or it's very hard to run a business. Some people do it, but it's very hard to run [00:15:05] a business that.

Is trying to turn itself into a real [00:15:10] business just based on documentaries or non returning programs. What you need [00:15:15] to know is that you're creating a whole catalog of programs that are coming back [00:15:20] year after year, right? So that you, you, you know, that [00:15:25] you, your overheads are gonna be covered, uh, largely by those returning [00:15:30] programs and all your energy is going into creating new programs so that you can grow and [00:15:35] take on more overhead, build, build your

James: portfolio, and

Stephen: build your portfolio.

So, you know, we, [00:15:40]

James: what was your first returning program?

Stephen: It was a program called Faking It. Faking It, [00:15:45] and it's probably the program I still love the most in many ways. Um, that's very famous. [00:15:50] It, well, it, it won the BAFTA two years in a row, and it was, it was much loved. What [00:15:55] was interesting about it, and it goes back to that point about explaining the difference between filming [00:16:00] things that are happening anyway and filming things that you've created.

And so [00:16:05] in faking it. It was actually my wife's idea. She said, I said, we need some ideas for [00:16:10] formats. And she said, why don't you do Pygmalion for real? Right. That's good. That that was [00:16:15] it. That was all she said. But I had to work out how to interpret that. Yeah, that's good. [00:16:20] I like that. And then, uh, I had to persuade channel four to commission it, which they did, [00:16:25] uh, as a, as a one-off.

It's a pilot, but with the intention that if it [00:16:30] worked, we'd make more of them. And it was essentially an idea where somebody would be taken from [00:16:35] one walk of life and they would be trained over a month. They would [00:16:40] live with a mentor. That was amazing. I can't believe these people would actually let these people come and live in their homes.

[00:16:45] So the in relationship. So, so they'd live with the real deal. They would live with the real deal. So the, the, [00:16:50] the, the first one that was, we did actually do one where a, a a, a girl, a shop [00:16:55] assistant, had to fake it, uh, as, as a high society kind of [00:17:00] lady. A real pig male. A real pig male. That was okay. Really took off when we did the second one.

[00:17:05] And we took a, a, quite a, a slightly delicate, uh, Oxford. [00:17:10] Graduate, undergrad, I can't remember where, which one he was now. And he had to fake it as a bouncer. [00:17:15] And I'm already wishing I'd seen that.

James: It's a great program.

Stephen: That's [00:17:20]

James: called Great Pro. Can you find it on YouTube still? What's it called? You

Stephen: can find it on, on channel four.

All the [00:17:25] faking episodes are on there. Are they on on there? Fabulous. On, on whatever. It's [00:17:30] of Fing it on their iPlay. It's not their I play, it's their Channel four player. Yeah. [00:17:35] And it, that episode was called Alex The Animal.

James: Right. Okay. Well that's one to look up [00:17:40] everyone. And he, he,

Stephen: he, he had, and he, he had to learn how to fake it [00:17:45] as a announcer.

Yeah. And. What they would then do, they would have to then [00:17:50] take part in the competition at the end where they would be competing against [00:17:55] experienced practitioners in whatever they was real bouncers. They were doing real bouncers in that case. I [00:18:00] was see, and there would be a panel of judges who would be asked to judge between them and [00:18:05] they would pick whoever they thought was the best bouncer or best.

Um, we, we, we, we had [00:18:10] a burger flipper her to become a top chef.

James: Right.

Stephen: Or, uh, I mean there were so many. [00:18:15] Then at the end we would say to the judges, oh, by the way, if we asked you and told [00:18:20] you rather that one of the people that taking part in that competition. I [00:18:25] only learn to do this skill four weeks ago.

Would you be surprised? And they [00:18:30] go, yeah, I can't believe anybody could do that. And they could. You spot that person. And very often they [00:18:35] couldn't. Yeah. And that was success.

James: So this, but this is inspiring for anyone who wants to learn a [00:18:40] new skill in life or you know, transferrable skills in work and all sorts of applications.

Absolutely. [00:18:45] And what was so, it's entertaining and inspiring actually.

Stephen: Exactly. And it was, that's why I, the program was so [00:18:50] loved because it showed you. And it's very purist, the kind of teach a [00:18:55] pupil relationship. And because they had lived together and because we would get the [00:19:00] mentor to be watching a live feed of the competition [00:19:05] and they would be so wrapped up.

I mean, we had, we had a punk rocker who had to conduct the London [00:19:10] Philharmonic and he knew he couldn't read music at the beginning of the four weeks. And [00:19:15] did this succeed? He succeeded. That's, that's so

James: good to know. Yeah. Um,

Stephen: but [00:19:20] 'cause really it was about nothing. Who cares whether they faked it. Yeah. But the mentor didn't [00:19:25] want to let down the pupil, the faker.

Yeah. And the faker didn't want to let down the mentor [00:19:30] and they really cared about it.

James: Yeah. Yeah. Well that was a huge success. So you, [00:19:35] so when you started Studio Lambert, I think in 2008, is that, what was [00:19:40] your first Studio Lambert um, project? Our

Stephen: first Studio Lambert project [00:19:45] was a documentary about something to do with Michael Jackson and we got sued and [00:19:50] Oh, I thought we were about to,

James: oh, so that didn't go so well.

Stephen: I thought we were gonna [00:19:55] is no, this is a good story because obviously I started this, we were steps in the high court really? And, and, and, and we thought, oh, [00:20:00] this is gonna be the end of the world. And then suddenly one of our hardworking legal [00:20:05] team found a piece of paper that completely destroyed the other persons

James: case.

So you were on the [00:20:10] cusp. So this is interesting because I've obviously introduced you with all the successes that you are currently sort of [00:20:15] producing, but you had a moment where you nearly lost the. You thought, thought the business you'd only just [00:20:20] started. Yes.

Stephen: And this was a business we'd launched in 2008, which you probably remember.

Yeah. [00:20:25] Uh, was also the height of the financial crash. Yes. Crisis. So it wasn't great. I carried the

James: scars, Steve, [00:20:30] I certainly remember. Yeah. So it

Stephen: wasn't a great time to be launching a business and then to have this problem [00:20:35] with our first show. But then we got a commission for a program called Undercover Boss, [00:20:40] which, which

James: I remember I loved that program.

Stephen: Well, channel four ordered it. They ordered [00:20:45] three. And we thought, oh my God, thank God we've got three episodes. Three episodes. Yeah. A trial, three episodes. [00:20:50] It was so hard to find any company that would play ball. And in fact, [00:20:55] we, we, we, we, we, we, we've, we've found two. And then the third one, we were about to [00:21:00] start filming and they went bust.

James: Right.

Stephen: And so we only actually made two of them in that [00:21:05] first series, but. This was the crucial bit from those two episodes we made [00:21:10] for Channel four, which did All right. So what

James: were they, what were the stories? Just, can you remember what one

Stephen: was? A one was a, a holiday [00:21:15] company.

James: Right.

Stephen: The boss of a holiday kind, sort quite low rent, um, yeah.

Holiday [00:21:20] company and the other was a boss of a steelworks and going into, [00:21:25] but,

James: and they went in undercover. So people didn know where they were. They went undercover. Yeah.

Stephen: And [00:21:30] they went in to do the job of some of a new [00:21:35] entrant. And they would, and they would be learning what was really going on in the company.

[00:21:40] There had been a program on the BBC called back to the floor, which was somewhat [00:21:45] similar, but in that case, the boss was known as the boss. Yes. Our, our [00:21:50] big sort of twist was that our boss was, was unknown almost invariably, that [00:21:55] the people never spotted who the boss was. Occasionally that happened and then we'd make it part of the story.

[00:22:00] Anyway. What was, what made it special? What transformed our business was that we were able [00:22:05] to cut what we call a sizzle reel, which is a piece of tape. You used to sell a idea. [00:22:10] Sizzle reel. I like it. A sizzle reel. It sizzles away. Um, out of, out of the British, the [00:22:15] two British episodes that we'd made. Yeah.

We went to Los Angeles. Where we'd [00:22:20] started up in our LA office at the same time as launching in London. Right. Which was quite ambitious for a new [00:22:25] company and was, we were able to pitch it to the absolute top person [00:22:30] at CBS who loved it so much that she bought the show in the room to make an American [00:22:35] version.

Right. We made the American version. They ordered a full [00:22:40] series, so it was it easier to find companies in

James: America?

Stephen: It was still quite hard. It was still very hard. The first one. It's [00:22:45] always the first one. That's so down hard. Yeah. Because no one knows what the format is. No one was exactly. But there was [00:22:50] a lovely man called Larry O'Donnell and his wife persuaded him, her, her name [00:22:55] was Dare and she dared him to To do it.

Yeah. And Larry [00:23:00] O'Donnell was the Chief Operating Officer of Waste Management, which is a huge Right. American company. [00:23:05] And it was a great one for us because he was having to work the bins and do all shovel [00:23:10] kinds of whatever. Yeah. Deal. Deal with garbage and. The [00:23:15] show was then tested by CBS. They have a big testing facility in Las Vegas [00:23:20] and 2000 people watch all their pilots and decide what to go forward with and what to [00:23:25] do, what, you know, what should be the, what will be the next hit.

It rated so well in the [00:23:30] testing that the people back at CBS said, that can't be right. Tested again, and they tested [00:23:35] it again, it came back even stronger. That's good. At which point they made the decision to [00:23:40] launch Undercover Boss in the most coveted slot on American television, [00:23:45] which is the slot immediately after the Super Bowl.

Wow. Immediately after the Super [00:23:50] Bowl. The audience is a hundred million viewers now that, [00:23:55] so your new production company suddenly

James: found itself with a suddenly

Stephen: with this amazing slot.

James: Yeah. [00:24:00] But this is the power of good ideas.

Stephen: Exactly. Well

James: executed. I mean, this is what's happened that you [00:24:05] obviously, it was a great effort.

No,

Stephen: no, no. It was great. Uh, but it was still incredibly exciting and must been, and also when, when, [00:24:10] when you're launching a show after the Super Bowl, you're worried about two things. One, you don't want the [00:24:15] game to be kind of walk away so that everybody loses interest and stops watching, [00:24:20] but you don't wanna be so close that it goes into extra time because then your show's not gonna start [00:24:25] until 11 or 1130 at night.

This one fortunately was exciting, but [00:24:30] it was finished on time and we inherited this enormous audience. Some of the audience obviously [00:24:35] pale peer, the, the, the, there's an after the game kind of discussion show for 20 minutes, [00:24:40] but basically we inherited 40 million viewers and held them for the next hour, making it [00:24:45] the most popular post.

Super Bowl show [00:24:50] that that had been for years and years and years and probably ever since then, right? Uh, [00:24:55] and it meant Undercover Boss was this huge hit that we then made many, many episodes of [00:25:00] and gave. Sort of life to our company. It'd be

James: harder to do now, I think. 'cause people know what their [00:25:05] bosses look like because of social media and stuff.

Is that right?

Stephen: I think that's true. Yeah. I think that's true. We were very good at coming [00:25:10] up with reasons for Yeah, I mean, we would disguise the bosses and we would [00:25:15] trick people into thinking we were doing, we might have two people there, we were filming. Yeah. You, you, you, [00:25:20] we were quite good at making it hard for people to realize, but you're right.

I think social [00:25:25] media would make it probably harder.

James: So that's, so that's fantastic. So that's how you began. [00:25:30] So fast forward you, you've done Goggle Box. Where did that [00:25:35] idea come from? Was that

Stephen: sustain? Uh, well, sustain, sustain happened in 2000, in the [00:25:40] early two thousands. No, so in 2000 and, um, after a few years, a [00:25:45] a colleague of mine, uh, who's now my partner, uh, and, and, and, and Chief Creative [00:25:50] Officer, Tim Harcourt joined and at that point he was the head of development and he had the initial [00:25:55] idea for Goggle Box, and we went together to pitch it to Channel four, along with a [00:26:00] whole lot of other ideas.

This was our last idea at the end. That was almost throwaway, but [00:26:05] fortunately. Well, 'cause we thought a crazy idea. Well, that's

James: what I'm thinking. How did you sell that to [00:26:10] someone

Stephen: watching people watching television? We said, we said it's a great, it's sort of interesting, [00:26:15] what we have realized, what made was that television watching was unusually [00:26:20] intimate.

Situation. The people that you sit and watch television with

James: Yeah.

Stephen: Are people [00:26:25] that you tend to be very close to. Yeah. And, and actually it's quite an intimate,

James: so [00:26:30] that was another insight actually. And it was,

Stephen: and and also we weren't quite [00:26:35] sure when we first sold it. And then we, we were given some money to make a little sort of test tape [00:26:40] of 10 minutes or so.

We weren't quite sure whether this was a kind of a show about these people's [00:26:45] lives or whether it was a TV review show.

James: Right. But

Stephen: it was, as we filmed [00:26:50] it and then started playing with it in the, in the cutting room, we was, no, we've got to, we've gotta [00:26:55] sell this as a TV review show. If you don't sell it as a TV review show, people are confused.

[00:27:00] But you'll learn about these people slowly. Yes. And if you pick the right people, they [00:27:05] will be entertaining. They will be, they will, they will reflect the kind of [00:27:10] diversity of Of, of Britain.

James: Yeah.

Stephen: And people will eventually kind of. [00:27:15] Well, hopefully quite, it's also

James: quite fun seeing how people react to stuff.

Exactly. How different that could be. How different, but also how [00:27:20] similar it is.

Stephen: Yeah. And that's, that's very interesting. I mean, the hardest thing about Gogglebox, [00:27:25] and I thought we, we probably wouldn't pull it off, is that it's to a [00:27:30] large extent a comedy and comedy's all about com. Brilliant editing, uh, [00:27:35] and, and comic timing, uh, which you achieve in the cutting room.

But you've got [00:27:40] no time to edit Goggle Box because it has to be filmed and edited within the week. [00:27:45] Right. So, you know, we start filming Goggle Box on, on, on a, on a Friday, [00:27:50]

James: right?

Stephen: We're filming on the Saturday, Sunday, Monday, Tuesday's about the end of our [00:27:55] filming period. We're starting to edit from the Monday of that week.

James: [00:28:00] Right.

Stephen: So stuff is coming by Wednesday. We've gotta have Wednesday night's, gotta [00:28:05] be getting close to a cut. Thursday we show it to the channel.

James: Yeah.

Stephen: Then on [00:28:10] Friday morning, we're, we're, we're, we're locking

James: stressful,

Stephen: and [00:28:15] then you're on air on Friday, and then it's, but then you're already filming the next one you do again.

James: Yeah. So you've [00:28:20] gotta have really good editors and, and you have to have

Stephen: amazing editors. You have to have a brilliant team. And [00:28:25] fortunately we did. You've developed

James: that. Yeah. And

Stephen: now they, they're so well versed in all this, [00:28:30] that. It isn't stressful. Uh, or at least it's not crazily stressful. [00:28:35] And the team are, you know, has a rhythm.

Has a real rhythm, and they enjoy making it [00:28:40]

James: so forward to today. I mean, we are coming up to the [00:28:45] conclusion of celebrity traitors. I mean, this has become a sort of national news stories in the [00:28:50] newspapers. You've been on news night talking about it. Front page of the sun today. Yeah. Front [00:28:55] page of the sun. I was standing in a queue.

I know. There just little thing on the front page. People were talking about it. You know, a little thing

Stephen: [00:29:00] on the front page.

James: A main story. It's the front

Stephen: page. Yeah. So this

James: is an amazing thing. [00:29:05] What, what's going on here in your view? What, what, why is this really captured our imagination?[00:29:10]

Stephen: It's a damn good game.

James: [00:29:15] Yes,

Stephen: very well executed with, uh, [00:29:20] unusually, uh, good celebrity cast. A cast that of the kind that you [00:29:25] would never normally see in a celebrity reality show.

James: So as a [00:29:30] producer, you pulled that together?

Stephen: Well, the cast came. So what

James: was key to getting the cast? How do you [00:29:35] do that?

Stephen: The, the key to getting the cast was the strength of the civilian versions.

Everybody, you [00:29:40] call 'em

James: civilians and celebrities. We do. That's language a bit like some of the [00:29:45] sizzles and ground bait. That's another phrase. Yeah. So, yeah, [00:29:50] so, so the civilian versions were very successful.

Stephen: The civilian versions were successful and [00:29:55] very much light by people particularly. Or relevantly, [00:30:00] the, the celebrities themselves had seen it.

Yeah. And, and everybody who took part in [00:30:05] celebrity traitors w were, they were all fans of the show. [00:30:10] Uh, yeah. And, and they went, they weren't doing it for the money. I mean, they're paid, but it's compared to how [00:30:15] much people are paid, say on, I don't know, other shows like, I'm a celebrity, get me out of here.

[00:30:20] They're paid much less. Uh, and, and the prize is for charity,

James: isn't it? And

Stephen: the prize is for [00:30:25] charity. So the real reason, the real question, I suppose is why did they all like this show so much? [00:30:30] And that goes back to what's interesting about the program. I suppose what's interesting about [00:30:35] it is. It turns out it's fascinating [00:30:40] watching people lie [00:30:45] and being given license to lie.

I think one of the sort of great [00:30:50] qualities about traitors is that in many reality shows people end [00:30:55] up sort of betraying others and that betrayal [00:31:00] or sort of deceit is, is is sort of revealing [00:31:05] of their character and it can sort of leave a bad taste to the viewer. They think, oh, awful people [00:31:10] here, people are given license to lie much as you're given license to lie [00:31:15] in the poker game so that if you win as a traitor, people [00:31:20] congratulate you.

Because you've played a good game. They don't say, oh, you, you mean you lied [00:31:25] throughout? No, they say, well done. You, you, you played the game, you played the Well,

James: apparently Paloma face [00:31:30] not very happy. Well, maybe there are some exceptions. Well, maybe that's a good story. I, I dunno. [00:31:35] But yeah, so I

Stephen: think from, and then I think the fact that, [00:31:40] you know, the, one of the classic things of Greek drama was, was, is [00:31:45] is dramatic irony where you, the viewer know more than [00:31:50] the, than than the participants.

James: Oh, so that goes right back to Greek drama. Does it? Oh, I definitely think so. I [00:31:55] love that because we know who the traitors are. Obviously we know who the traitors are and it's, and I think

Stephen: dramatic irony is [00:32:00] actually key to a lot of. Programs that we've done. I mean, undercover Boss is dramatic irony. Faking.

It was [00:32:05] dramatic irony. Yeah, of course. That's the connecting theme in a way. Right? Back to Greek. That's so [00:32:10] interesting. Back to the Greeks, they had all the secrets. Yeah. And I think the fact that we, the [00:32:15] viewers know who the traitors are and we can't quite believe that the faithful can't spot it [00:32:20] and it makes us No.

And how dogmatically can be and wrong. Exactly. It is so interesting as well. Yeah. And then that becomes so [00:32:25] interesting to to watch. The way a group comes to a [00:32:30] conclusion the way, I mean, it does make you question the whole jury system [00:32:35] changes. And also think

James: running a, a company boards anything, how a group becomes so certain about something that can be [00:32:40] so wrong.

Stephen: And, and, and, and, and also how they seize on evidence to support [00:32:45] their fear is that, I mean, the, the point about traitors [00:32:50] is that the traitors do start doing things that is real evidence. [00:32:55] And the skill then of the faithful is to spot it, to recognize how significant it is and to [00:33:00] persuade the other faithfuls that this is real evidence.

No, but at the beginning of the show, there's [00:33:05] no evidence. No. And so it does, it, it it's, it's, it's such an un [00:33:10] It, it's, it's, it turns out that that's very entertaining watching [00:33:15] people create theories. It's, I suppose it's a sort of, uh. [00:33:20] Uh, it's a, it just like, it would be an in fascinating and, uh, to, [00:33:25] to, to watch how a jury works.

James: Yeah. Well, 12 Angry Men is a very famous film. Well, indeed. [00:33:30] So, so I'm thinking about this, the, the, and then there, the current show. It hasn't gone [00:33:35] unnoticed, especially from colleagues of mine who've watched all of your traitors series. The, [00:33:40] the celebrity traitors took quite a lot longer to spot [00:33:45] spot the, the, the traitor than the [00:33:50] civilian.

Uh, that's just because I think the celebrities are very good at being traitors. You think, [00:33:55] well, you've certainly had some good ones. I don't Yeah, that, that I would agree. I mean, they were very skilled [00:34:00] when I, so, so the ities are better traitors. That's what

Stephen: Well, when people get frustrated [00:34:05] with, with, with, with, with, with the faithful and think, oh, they're not very good [00:34:10] faithful.

Multi counter argument is they're very good traitors. Yeah. Yeah. And I, and I, and [00:34:15]

James: I think Kat, Alan are very good traitors, who are still in very exceptionally good. Are [00:34:20] exceptionally good. So, so we'll wait with great interest to see how this works out. And then [00:34:25] you've also got coming out at the same time that traitors concludes your new [00:34:30] celebrity race across the World Series.

So what's made that, that, that's [00:34:35] another huge hit. What, why is, is that dramatic irony again, or is that something else?

Stephen: Definitely not [00:34:40] dramatic irony. We Oh, definitely not. We all know what's going on. I mean, they, they, we know as much as [00:34:45] they do. Well, I think it speaks to people's [00:34:50] love for travel, but, or sort of authentic travel.

But I think the key thing about that [00:34:55] show is that. You know, it's, it's, it's a show about a journey in [00:35:00] the relationship of the people that are, the pairs that are, are taking part in the [00:35:05] competition as well as a physical journey. And I think the, the way in which the [00:35:10] team who make it skillfully tell that story of, of how, that the [00:35:15] relationship between father and son or two friends or husband and wife, how, how, [00:35:20] how, how, both a backstory, but also how it changes.[00:35:25]

In the present tense as they go on the journey. Yeah. Is, and we [00:35:30] imagine how we would be in that. And we imagine how we would be. Yeah. And you [00:35:35] see, you see the world in a way that feels sort of [00:35:40] unfiltered. And I think also people are so touched by [00:35:45] how generous strangers are and the kind of the small things or [00:35:50] sometimes the big things that people do to help each other.

So it's a, it's a very [00:35:55] heartwarming and uplifting show that. Has just the [00:36:00] right amount of kind of tension and, and, and, and excitement as they, [00:36:05] as they compete to get to the next checkpoint. You are, [00:36:10] you, you, you, they have all kinds of mishaps and problems getting to those [00:36:15] checkpoints that they have to overcome.

It's, yeah, I mean it's, it's, it's, [00:36:20] it's just a great authentic journey show that has lots of journeys going on, [00:36:25] uh, in addition to the obvious physical journey.

James: An [00:36:30] odyssey, if we go back to the Greeks. Yeah. So that's another, uh, yeah. [00:36:35] Classic structure. I, I guess so you've got a great advertising campaign coming out to support these [00:36:40] two shows you just mentioned to me before we started, what's it called, Steve?

Stephen: Oh, well, I dunno. [00:36:45] The, the, the, the, the, the, the strap line for it is run. Lie, [00:36:50] enjoy. So you run in race across the world, [00:36:55] you have to lie in celebrity traitors and hopefully together the two are shows that you [00:37:00] will enjoy. It's just unusual because celebrity race across the world is [00:37:05] launching at eight o'clock on Thursday on BBC one, and straight [00:37:10] afterwards at nine o'clock, celebrity traitors comes to an end.

[00:37:15] Um, it's the final episode, so

James: to have two. So on Thursday I'm gonna be doing this, I'm gonna be [00:37:20] run, lie, enjoy. That's what I'm gonna be doing. And I think a few other people listening to this might be [00:37:25] doing the same thing.

Stephen: Oh yeah. We're expecting a very big audience for the final of the traitors. I'm sure [00:37:30] there'll be a very big audience for the, the launch of celebrity race across the world.

So Huge's,

James: my, for you and your [00:37:35] team on television, well, congratulations. I mean. I was thinking about this coming here. I mean, you have [00:37:40] entertained millions of people over more decades now, and not many people can [00:37:45] say that. And I, I think it's fantastic what you do. And, and I'm so pleased that these series are such [00:37:50] big hits.

'cause they deserve to be the one, the one that sort of, I found little surprising was the [00:37:55] Squid game, the challenge. 'cause I, I mean, I watched Squid Game and I thought it was the most violent show I've ever [00:38:00] seen. But you managed to turn that into a, into a sort of successful, uh, well [00:38:05] unscripted format. What made you do that?

And and how does that work?

Stephen: [00:38:10] Well, we were asked to do it by Netflix. Right. Uh, they had the [00:38:15] idea of wanting to Oh, so they came to you with this idea? They said, you know, 'cause it [00:38:20] Squid Game, the drama is their most successful show. It's got the, [00:38:25] of all time. Of all time. Ever since Netflix has started it, it, it's had a bigger audience [00:38:30] than any other

James: show.

It tells us a lot about human beings.

Stephen: Well, and they didn't expect it to [00:38:35] be that big. Right. I mean, they thought it was going to be huge in in in, in Korea. Yeah. But it just went [00:38:40] everywhere. It was an extraordinary show though. It was very unusual show. Yeah. And [00:38:45] unusually, it was a drama about a competition.

And the [00:38:50] man who is in charge of unscripted television at Netflix managed to [00:38:55] persuade his colleagues that, well, look, our biggest show is, um, is a [00:39:00] drama about a competition. Why don't we do the competition for real

James: with a few sort of [00:39:05] changes?

Stephen: With a few changes? I mean, unless you, that one gets killed dressed, no wonder whether it was possible to kill [00:39:10] people.

But our lawyers said, no. It's gonna be really tricky

James: if you do that. Yeah. Right. So a few important [00:39:15] changes.

Stephen: Yeah, I mean, it, it, I think people are, were fascinated by that world. There's a [00:39:20] huge fan base that, that we were loved the, the, the drama and [00:39:25] they were interested and wanted to see what a real version was like.

Because again, like a lot of these [00:39:30] shows, like you were, when we were talking about race across the world, people are thinking, what, what would it be [00:39:35] like if I was doing it? Yes. And again, I think with Squid Game, it was always, what would it be like if I was in [00:39:40] that situation? And the show enables you to see what it would be like in a way [00:39:45] that I think people find.

Compelling. It, it we, [00:39:50] you know, obviously we, it was a huge

James: financial prize as well, like in the it's, and that,

Stephen: that was the [00:39:55] kind of unscripted 5 million. That was the kind of, how do you, obviously we're not going to kill people, [00:40:00] so what do you do that somehow. It gives the same sense of, [00:40:05] oh God, this is terrible.

I've been eliminated. Well, I think it, the, the, the size of the [00:40:10] prize was crucial to that. It meant that everybody, you, you, you, you don't die, [00:40:15] but your dreams die when you get eliminated.

James: That's somehow worse. [00:40:20] 4.56 million is not gonna be yours, Steven. You're out. It's not. [00:40:25] Yeah. Okay. And

Stephen: only one person is going to get it.

One person

James: gets it.

Stephen: And [00:40:30] that's, I mean, it's a very hard show to make because [00:40:35] if you are making the scripted version, you've got a script [00:40:40] and there's a pretty, pretty useful things. That means you know who's going to win. Yeah. Yeah. And you know which [00:40:45] characters to follow. 'cause they're the ones who are going to get, and you don't do, you do your and we don't.

Right. And so we are having [00:40:50] to, it's a. Putting it together and shooting it is, is, [00:40:55] is a bit like a relay race. You're sort of, you, you, you build a pattern and you're [00:41:00] following somebody that you get interested in and then they get eliminated. By that [00:41:05] point, you've hopefully they, the bat has been passed to somebody else.

Right. And so as you get [00:41:10] closer towards the end, the characters that will take you to the end have started to [00:41:15] emerge both in the filming but also in the edit. Right. 'cause it's not like we can just, [00:41:20] there's so many people, there are so many people that 450 something. [00:41:25] 456. Yeah. That. We can't film them all.

So it's not like we can go back and go, oh, [00:41:30] well we know who's going to win. Let's get all the footage of what they were doing at the beginning. We just don't [00:41:35] have it. We don't, and if we do it, they'll kind of, there'll be brief shots. They won't be, they won't be [00:41:40] interesting stuff that will make us kind of build them up as characters.[00:41:45]

James: So that's a, in production terms, a complicated task. Very complicated. Yeah. [00:41:50] So I'm, I'm interested, a couple of things just before we put traitors to bed. Keeping it [00:41:55] confidential, I mean, you know who's won, you're sitting opposite. I'm not gonna ask you [00:42:00] obviously, but how do you make sure that doesn't leak out?

I mean, that's a huge thing 'cause we are all [00:42:05] on sort of tenor hooks. Do you get 'em to sign some, I mean, how do you make sure that happens? Because [00:42:10] it would obviously spoil it.

Stephen: Yes. I mean, everybody's has contracts that say you can't [00:42:15] talk about the show who, whether they're celebrities or civilians. Yeah.

Some of them are [00:42:20] better than others that Yeah. You their contracts and sticking to them. Fortunately, [00:42:25] when it comes to the press, they don't want to ruin it for, so they might have heard a rumor, but they're not gonna, [00:42:30] they might have heard they're not going to publish anything. Yeah. There's always a danger that people will say something if [00:42:35] they think they've heard something on social media.

A [00:42:40] rumor on social media isn't very definitive. So people, it doesn't look that different to [00:42:45] just somebody saying, oh, I think they're going to win. And

James: Yeah. Yeah. So you do need the sort of [00:42:50] goodwill of the press. You do need the goodwill of the press. But, but, but they don't want spoil it for everyone.

Stephen: They don't [00:42:55] wanna spoil it for everyone.

It is also, you know, people watch Hamlet over and over again. I mean, [00:43:00] in the end of the day, I don't necessarily know that if you did know who was going to win, it would [00:43:05] be the end of the world. You're still fascinated to know how, how that came about. They, how, [00:43:10] how the winners were able to win. You don't, you don't need to actually have that as a [00:43:15] secret.

What you're, what all, all, all stories. What do you wanna know is sort of how did they, how, [00:43:20] how did it come about rather than actually what the final result was. Yeah. But yeah, I mean, [00:43:25] we put an awful lot of effort into keeping it secret and we, and, and I've just

James: a sort of production [00:43:30] question, how long is everyone in the castle for?

Because aren't they sort of cut off from the outside [00:43:35] world and they go and film there, but they can't off from the several weeks.

Stephen: Well, no, each episode [00:43:40] is shot in a day.

James: Okay.

Stephen: I mean, the first episode tends to get shot in [00:43:45] more than a day because they arrive and then there's a whole lot of press stuff you've gotta do, do.

But how long

James: would they [00:43:50] typically be there? Two weeks or?

Stephen: Well, if they, if they, if they, if they get [00:43:55] murdered or banished early on Yeah. They're not there for very long. At 12. No. Okay. The ones who [00:44:00] survived the end, you're end then, you know, it's, it's, it's a, the, the shows tend to [00:44:05] be like, well, the celebrity one's nine episode, the civilian one is 12 episodes, so [00:44:10] you're there for 12, nine days plus a few extra days.

Yeah. Plus you arrive, [00:44:15] you know, to get acclimatized. I mean, so it's, it's, yes. It's about two weeks.

James: Yeah. And [00:44:20] that's sort of intense engagement.

Stephen: Yes.

James: Yeah,

Stephen: it is. It is very intense. I mean, [00:44:25] you can tell,

James: I mean,

Stephen: looking

James: at it, well, I think

Stephen: crucially with, with all these shows, it's the same with Squid Game. [00:44:30] You create a world where we try not to be [00:44:35] in there with them.

Right. As much as possible. You as the production team? We, the [00:44:40] production team. Yeah. They're in the there. The, the camera coverage is [00:44:45] such that. They just get on with it. I mean, they get dropped off. They kind of know. [00:44:50] That's another reason why it's very important that you do the whole episode in a day.

'cause they're sort of picking up [00:44:55] the rhythm Yeah. Of the show. They know and they get dropped off. They go to breakfast, [00:45:00] they know what to do. I mean, CLA comes in and tells 'em a little bit. They know when the clocks [00:45:05] like, oh, it's time to go home. I mean, you don't need somebody to keep telling them what to do.[00:45:10]

And we don't ever tell them, go and do this, or Why don't you go and say that? Or, [00:45:15] so it has its own energy in its own. So it has its own energy. 'cause the most important thing is its authentic. [00:45:20] So there's no direction going on, or No, I mean, we are trying to work out what we think might happen. [00:45:25] We're all the time anticipating, but that's not the same thing as trying to tell them what to, [00:45:30] you know, telling them what to do.

James: Yeah.

Stephen: And also remember, it's, [00:45:35] it's, it's, it's a competition. I mean, particularly with the civilian versions, people are winning quite a lot of money [00:45:40] and so. With any competition, there are very strict rules. I mean, with Squi game, the [00:45:45] challenge, the amount of money's enormous. So the rules are equally very, very strict.[00:45:50]

You know, we, you can't interfere in any way as a producer [00:45:55] in a

James: no. You can't have a favored Exactly. Faithful or anything like that. No. [00:46:00] Stephen Fry gets it. He gets it, I suppose. Indeed. Yeah, indeed. [00:46:05] Looking forward, I mean, I, I meet lots of young people who say they wanna work in [00:46:10] TV or they want to go into film and it.

It isn't obvious how [00:46:15] someone might do that. And I bet you get a lot of people coming to you, but if someone was interested in this [00:46:20] space, I mean, you, you went into it through an unusual route, you said doing a PhD about [00:46:25] channel four, um, and often unusual routes are the best. But what should a young [00:46:30] person who's interested in this space, 'cause it is a huge industry now, uh, and, and [00:46:35] something that Britain clearly excels at, thanks to you and others, what should a young person be [00:46:40] thinking about or, or trying to sort of learn or what experience might they usefully [00:46:45] get to, to start that journey?

Stephen,

Stephen: the obvious one is watch television. [00:46:50] It's amazing television. It's how many people

James: really? Isn't that obvious? They come to you and they haven't watched it? Well, you

Stephen: [00:46:55] start asking them about television programs and they, they haven't watched a [00:47:00] lot of things. That's, yeah. Uh, try and watch television, not just television today, but, you know, [00:47:05] there's so much historical, I mean, interesting television.

James: Yeah. Whether

Stephen: it's [00:47:10] dramas or reality shows or whatever, that give you a historical perspective of where television has [00:47:15] come from. Develop your critical faculties, watch television and start thinking [00:47:20] about. Why, why do I like this program? What's making it work? Or why don't I like this [00:47:25] program and what's making it not work for me?

How would I change this program that's not working for [00:47:30] me to make it better? Learn how to talk about television so that you are [00:47:35] discussing it as a, as, as, as a, as a, as a, as a medium through which if you are [00:47:40] interested in working in it, you understand what are its constituent parts and [00:47:45] which bits, well, all bits are crucial to making it work.

But you know, [00:47:50] why didn't, why did they get it wrong? I mean, with scripted programs, it's [00:47:55] amazing because so much energy goes into the script and yet sometimes you [00:48:00] watch things and you think, why on earth is this ever get ordered? 'cause the script was terrible, but [00:48:05] obviously somebody thought it was good, and why?

Why did. Why would they have thought it was good? And [00:48:10] also, what is a particular program trying to do? You know, obviously every programs are doing different [00:48:15] kinds of things, not just in terms of what they're about, but also what they're doing [00:48:20] in a schedule. Because the television is still [00:48:25] largely still commissioned for a linear schedule, even though so much is watched, um, [00:48:30] on, on, on streaming platforms, but even on a streaming platform, even on Netflix, they're still, [00:48:35] you gotta think about, well, what are they actually doing?

How are they spending their money? What percentage of [00:48:40] their, of, of their money are they spending on kind of low cost programs? [00:48:45] What kind of programs are they buying that probably don't cost that much? [00:48:50] What are the, why are they deciding to spend a lot of money on those big ones? Just read about [00:48:55] television, watch television, learn to talk about it.

Immerse yourself. [00:49:00] Immerse yourself. That's what, that's the number one thing.

James: Yeah.

Stephen: The number two thing is, [00:49:05] yeah, I mean, you. It is hard. There's so many people want to work in. That's what I'm [00:49:10] seeing. Yeah. So, but it's equally much easier today to [00:49:15] make something and to put it up on YouTube or to, to [00:49:20] put it elsewhere.

I mean, on Instagram or whatever. What's it called? A

James: sizzle tape. Well, a [00:49:25] sizzle tape.

Stephen: Make your own sizzle tape. Make your and sizzle tape of, of, of your skills. The sizzle. Well, I was thinking

James: about your CBS [00:49:30] experience. I mean indeed, indeed. I know. I'm, that's you. I

Stephen: understand. Yes. Yeah. But I mean, you don't have to just make a [00:49:35] sizzle tape.

You could, you could make a little. Come up with something [00:49:40] that if you, if you, if you a comedy of some kind going into, people [00:49:45] can do amazing things with very little these days with phones and they can show with phones and they can [00:49:50] show their creative sensibility and skills. I mean,

James: [00:49:55] this is, but this is so exciting in a way.

'cause you can do this with nothing really. Yes. You can start from, of course. You don't, there are [00:50:00] no barriers to entry. No. You don't have to have huge amounts of cap idea. No. I mean, you've got interested

Stephen: in television, one television. [00:50:05] Think about two people that you know, who you think are very funny and just arrange for them to talk to each other and [00:50:10] film it and edit it.

'cause it's also not very difficult to edit and put it up on YouTube. You say, [00:50:15] look, I, and then you can show people stuff that you are doing. Um,

James: yeah.

Stephen: Then [00:50:20] Sommer

James: yourself, then get started in some ways. Then get started

Stephen: in some way. And then [00:50:25] the hardest bit of all sort of latch onto somebody who's a mentor.

I mean, most people in [00:50:30] television have some, at some point, point early in their career, they've found somebody that [00:50:35] they've managed to film, build a relationship with so that [00:50:40] those, that person sort of helps them get going and, and, and yeah. And, and, and [00:50:45] sort of helps them get in the door or, or, or get break a bit of encouragement

James: or some [00:50:50] introductions and, yes.

Yeah. Advice. But I mean, none of that's easy. No. But, but it's all [00:50:55] eminently possible.

Stephen: It's all imminently possible if you are really driven. I'm, [00:51:00] yeah. I'm often surprised at people's lack of interest in kind of [00:51:05] really understanding what television is and where it's come from. And I think if you, which [00:51:10] is

James: where we began our conversation.

Stephen: It is.

James: Yeah. So you think that's, so understanding that [00:51:15] is critical, really. You think? Well, I

Stephen: think it, it, you know, it's, well, you've

James: helped explain it [00:51:20] actually in this, in this conversation. For anyone listening, they've gotta start already.

Stephen: You don't need to know where we've come

James: [00:51:25] from and what's been done.

Can I ask you, you mentioned, I mean, you mentioned the importance of watching television, you [00:51:30] other unscripted shows not be made by you, that you think [00:51:35] that you really like.

Stephen: Oh, well, all the hits that we don't make, I wish we would've [00:51:40] made. So which ones are you thinking of? That's just interesting. Well, I mean, bakeoff is a huge hit.

Bakeoff Who wants [00:51:45] to be a Millionaire? Yeah. In America. Survivor. I mean, yeah. I, I, [00:51:50] I'm, I'm very, it's really hard to make a popular, [00:51:55] successful program. I bet. Because. I, I'm [00:52:00] often amazed because when I was a documentary maker at the BBC, there [00:52:05] was always a kind of, oh, well, we make the real stuff. You know, we're telling the people, the documentary [00:52:10] team documentary, we're telling people about how the world is, we're not making kind of [00:52:15] sort of entertainment stuff,

James: but this is psychology we've been talking [00:52:20] about though, in Exactly, and, and,

Stephen: and the idea that, oh, well, you [00:52:25] can just default to popular easy stuff.

It's the hardest thing in the world to come up [00:52:30] with something that it, it's much harder in my mind or in my experience [00:52:35] to sit around with clever colleagues and try and design a new, popular, [00:52:40] returning entertaining program than it is to say, go and make a documentary about. [00:52:45] I don't know anything.

Policemen in South Africa, policemen in South Africa, because essentially if I want [00:52:50] to make a program about policemen in South Africa, okay, well I've gotta have, I gotta find some charming way [00:52:55] of persuading the people who are the gatekeepers to let us in.

James: Right?

Stephen: And there are [00:53:00] all kind of techniques for how you do that and, and, and, but they're essentially [00:53:05] practitioner.

Skills. I mean, there's skills about how to persuade people, how [00:53:10] to be around, how to win people's trust, how you start filming, what kinds [00:53:15] of things you film that will make a, a bit of narrative for you. How you then put all that [00:53:20] together in a cutting room. All that is skills that you kind of start to [00:53:25] learn as you're in television.

You get better and better at it. But that's not a, that's an [00:53:30] easier process I still think, than to sit there and kind of with a piece of blank [00:53:35] paper. Let's just come up with something now that is going to. Be a [00:53:40] design for a program that is a [00:53:45] format that will repeat that there's sufficient variation so that [00:53:50] people aren't watching the same thing over and over again, but they are watching something that is [00:53:55] essentially repeating.

I mean, each season of traitors the same format is happening. [00:54:00] Yeah. It's just that it's designed in such a way that there's sufficient variation [00:54:05] because of the change of the cast and because of the way the game plays out. [00:54:10] So that is a very, so to lead a challenging, [00:54:15] I can see that it's a hard thing to do.

That is a creative process, I think, than, than the [00:54:20] practical skills of actually making say, a documentary.

James: Talk me through that a [00:54:25] bit then. So you have a group of people, but how many of you would sit around with this blank piece of paper and, and, and [00:54:30] how do you sort of. I, I don't like the word is ideate or create some [00:54:35] new format.

I mean, you've obviously done it a number of times.

Stephen: I've done it a lot. I mean, these days, [00:54:40] I, I, I, I, my, my younger colleagues do most of it. I tend to get more [00:54:45] involved as we get to the point where an idea is sort of at the point where we're trying to [00:54:50] sell it to the buyers. And that's where people

James: have sum up the money, where

Stephen: you, where you've got, I mean, the [00:54:55] hardest thing in television, I think is persuading somebody to give you the money to make a [00:55:00] television program.

James: So what are we, how much money are we talking about? Just so people understand, [00:55:05] uh, race across television. The world programs

Stephen: used to be in the hundreds of thousands. I mean, the kind of [00:55:10] programs that we make now, they can be over a million. A a an episode. Episode. [00:55:15] And I mean, in the case of something like Squid Game, the challenge, it's, you know, more than, I [00:55:20] mean, it's millions as opposed to an episode rather than, uh, right.

So it's. [00:55:25] And so someone's writing

James: you a big check

Stephen: at this point. They're writing you a big check to buy [00:55:30] this out. We made a decision, my partner, Tim and I, a few years ago, to just [00:55:35] concentrate on big shows because we had the view that, [00:55:40] of thinking about it from the buyer's point of view, the buyers are going to lose their jobs [00:55:45] if they buy very expensive shows and they don't work.

And so [00:55:50] they're taking a huge risk. And yet they know that in [00:55:55] order to kind of stand out, by and large, they need to take these big [00:56:00] risks because those big shows are, the shows that are, are are ones that are going [00:56:05] to appeal, get on the front page of the sun, get on the front page of the

James: sun. Yeah.

Stephen: And so. [00:56:10] If you are in the, if you're going to be a buyer buying big shows, you're only [00:56:15] going to buy from people that you know can actually deliver and are not gonna screw up.[00:56:20]

So even if you've got a good idea for a big show, if you don't know how to make it, [00:56:25] or if you haven't got the track record that says you can make it, then you are very [00:56:30] unlikely to actually get that board right. And so, so you need the combination that com [00:56:35] once you can get into that club, once you're in that club of, we make big shows and we can deliver and they're [00:56:40] good.

It's surprisingly not as crowded a club as other parts [00:56:45] of television. Yeah. I'm thinking there's some barriers to entry

James: there. So that makes it a good business though. I [00:56:50] mean, it's, that does make you point of view of business. You're

Stephen: concentrating on big shows, [00:56:55] then it's, there's less competition. [00:57:00] And it's also, you know, the, the, the, the, the, the rewards are greater.

James: [00:57:05] So I'm thinking about the Business Studio Lambert. Um, you've become part of all three [00:57:10] media, so they acquired your business, is that right? Um, and [00:57:15] just talk me through that because I mean, you've got quite an interesting business model as I understand.

Stephen: [00:57:20] Well, I'm constrained from taking too much about a business model, but fair enough.

We talked earlier on [00:57:25] about how television, independent television developed and how in the early [00:57:30] two thousands the independent sector finally got a better deal out of, out of [00:57:35] from with the support of government. And as a result, for the first time, [00:57:40] money did start to come into the sector outside money.

And as a result there's been quite a [00:57:45] consolidation process. And so a lot of independent production companies have been bought [00:57:50] and become part of big groups. And those groups are able to [00:57:55] kind of, um, avoid the sort of problem of. [00:58:00] Being too small, and so kind of feast and famine. If you are large enough, then you've got [00:58:05] enough of these returning programs and when something drops away, you've got something else coming [00:58:10] through and it's on a scale also enables you to have a, a.

If [00:58:15] television is either sold to buyers who take all the rights like Netflix, [00:58:20] or they're sold to program to people like the BBC or NBC in America [00:58:25] who just take the rights to their particular territories, that second group of, [00:58:30] of, of buyers are much better from an independence point of view because you then get the right to [00:58:35] sell the program and the, and the, the finished program and the format all around the world.

[00:58:40] And if you are part of a big group, the distribution company will then be a very effective [00:58:45] seller of your tape and your formats to all the territories.

James: So that's why,

Stephen: and, [00:58:50] and that's how the, the benefit the sector benefits. I mean, how you retain [00:58:55] talent is, is, is, is difficult. And we've, we've come up with quite ingenious [00:59:00] deals that have enabled us to, uh, incentivize [00:59:05] everybody in our company, or not everybody, but all the key people to, to keep [00:59:10] staying and, and, and, and to do deals where there are, are rewards over time [00:59:15] that are, you know, depending on how well we're doing.

And [00:59:20] they, they, they, they, as well as the culture of the company have been the key things in terms [00:59:25] of, um, making us successful.

James: So just sort of [00:59:30] looking ahead a little bit, you know, as we come towards the end of the conversation, I mean, what excites you [00:59:35] most about the future of unscripted? I mean, it's obviously a world in which you are leading, but [00:59:40] what's next in this space?

Stephen: Well, the new big [00:59:45] thing, I mean, I dunno that there's a theme of what's going to excite me. I mean, [00:59:50] we are trying to take a lesson from Squid Game and seeing [00:59:55] other, um. Big, big existing IP and how we [01:00:00] can turn something that already exists as either as a, as a [01:00:05] game or as a, as a, as a big drama series and turn that into a big [01:00:10] unscripted show.

We're obviously coming up with new ideas ourselves, [01:00:15] uh, and, and, and we're looking for opportunities that [01:00:20] to, you know, to partner with the right people or to take something, I mean, where somebody [01:00:25] comes to you with an idea for.

James: So you are open to ideas from a, from the right places. [01:00:30]

Stephen: We're open to ideas that tend to come to us from a buyer rather [01:00:35] than from sort of individuals.

I mean, in other words, if a broadcaster like Netflix came to us and talked [01:00:40] about wanting us to do an unscripted version of squid game, that kind of thing. [01:00:45] Yeah. Rather than. Uh, 'cause I mean, we, we employ a lot of people. We [01:00:50] employ a very talented development team to create our own ideas. Yeah. So [01:00:55] every time we take an idea from, or if we ever took an idea from outside of our [01:01:00] own group, they our own inha.

In-house people, there's an opportunity cast, and [01:01:05] that's complicated. It's a dilution of, it's a dilution, so we tend not to do that. But obviously if a [01:01:10] broadcaster comes to us or a streamer comes to us with something and says, do you wanna make this into a, [01:01:15] into a show, then that's quite exciting and you know that then often it will, it will happen.

James: [01:01:20] Yeah. Well, as, as it did with Squid Game. A challenge. Lastly, Steven, that, is there anything [01:01:25] you wish you'd known at the beginning of your career that you know now that you could have told your. [01:01:30] Younger self.

Stephen: By Apple. By

James: apple, [01:01:35] yeah. I wish I'd known that as well. That's a very good answer. [01:01:40] I dunno what the equivalent is for the future, but there must be something out there for anyone to [01:01:45] keep an eye on.

Stephen: I don't know. Gosh, I, I, I listen back to a tape [01:01:50] of an interview I did when I wrote my book in 1982, and I [01:01:55] realized. I was so wrapped up in the subject matter that I, [01:02:00] I was describing the trees and I couldn't actually describe the wood. [01:02:05] And I think to be able to tell people when they're young, [01:02:10] immerse yourself in knowledge about whatever it is that you, you're interested in, [01:02:15] but then also be able to try to step back and talk about it in a, [01:02:20] in a way as if you are explaining it to your slightly deaf aunt, [01:02:25] rather than thinking that I need to [01:02:30] explain all this complexity and detail is something that [01:02:35] would've been useful for me to have appreciated quicker.

James: Why? Why do you say that? It's an interesting [01:02:40] answer.

Stephen: Well, I just think as a younger person, I was very [01:02:45] interested in the detail of things and that I would often have been asked about it, would want [01:02:50] to explain it in too much complexity. I mean, I think even [01:02:55] this conversation, you lose your audience or, well, I just think that people get bored unless you tell it in a very good way [01:03:00] or finding a way or, or, or, or also that it, it, um, if you're trying to [01:03:05] communicate whether.

In, in, in almost any situation, you have to be able to work out what is the actual [01:03:10] pithy important bits and, and, and being able to [01:03:15] develop your skill. It, it's no good thinking, you know, what the pithy important bits are if you don't [01:03:20] actually know the subject, but then if you know the subject in great detail.

Don't think you've [01:03:25] got to explain all that detail, but make sure

James: you know what the hy important bit are. Exactly. I mean, that's a [01:03:30] communication skill, isn't it? Yes, it is. So getting your message across or Yes. If you've got five minutes with [01:03:35] someone, what's the one thing you want 'em to know about you when they leave?

Stephen: Absolutely.

James: And that's sort of [01:03:40] sales skill as well, I suppose it is. Sales

Stephen: skill. And then I think that one ones sales skills got, I learned [01:03:45] my sales skill from 10 talking people into taking part in documentaries. [01:03:50] Right. And, and interviewing people in documentaries. I mean that you, you are listening all the [01:03:55] time and you're trying to, I think the best salespeople are, are, are listening as much as they're, [01:04:00] they're, they're, they're pitching, they're, they're, they're picking up all the signals of, of, of [01:04:05] what the, the buyer, the listener is, is, is, is reacting to what you're [01:04:10] saying.

And you are, you are responding to [01:04:15] those, but in a way that isn't like. Over-responsive. Well, I, I

James: remember going on a [01:04:20] sales course years ago and I was just told, you've got two ears and one mouth. So that was [01:04:25] quite a helpful pithy summary of that, what you're saying. Yeah, I agree. And, and, and what's [01:04:30] interesting, you know, you've been describing these, these wonderful programs and the psychology behind them, the importance of [01:04:35] ideas, but you've still gotta do sales.

And every business, whatever activity it is we're in [01:04:40] involves sales. That's what I mostly

Stephen: do these days is, is, is, is my energy, main [01:04:45] energy goes into getting things across

James: the line because some young people I meet say, oh, I don't wanna do [01:04:50] sales, or, I'm worried about doing so I don't wanna pick up the phone.

But everyone has to do that. You know, you are the top of [01:04:55] the tree in terms of television production. That's your main activity you just said. Yeah. And, and, uh, [01:05:00] is true for what I do and, uh, I mean, you might be a top. The lawyer. It's true for what they do [01:05:05] or people in business. So I think those skills, what you just said is very illuminating.

To learn how to [01:05:10] do that early on would help anyone in any activity. Absolutely.