Watch the episode

Listen to the episode

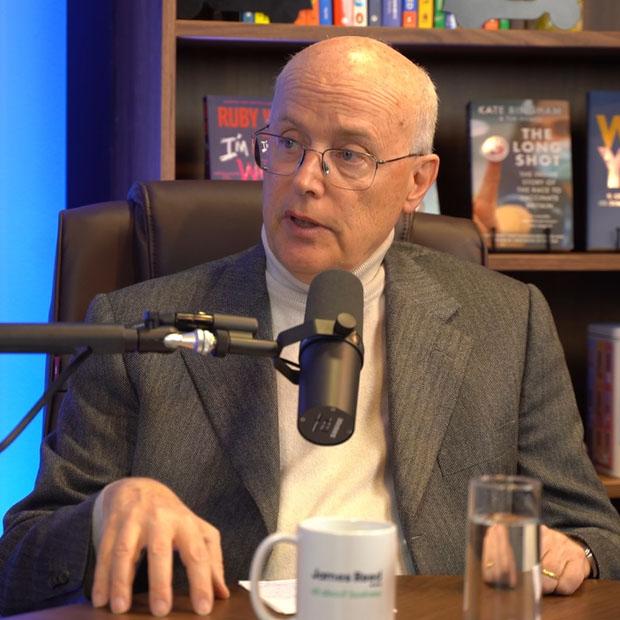

In this episode of all about business, James Reed is joined by Livio Manzini, Chairman and CEO of Bell Holding, a packaging and services company based in Turkey. We explore Turkey’s secret to efficient manufacturing, why trade wars are bad for everyone, and why ditching the Gregorian calendar might be good for business.

About Livio

Livio Manzini has been the Chairman and CEO of Bell Holding since 1993. It owns packaging and services companies, which includes Reed Recruitment Turkey. Livio is also an Honorary Chair of the Italian Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Turkey, where he fosters economic relations between countries by promoting bilateral trade, supporting SMEs, and promoting sustainability initiatives.

01:43 Who is Livio Manzini?

08:15 the Gregorian calendar

15:35 Bell Holding, Turkey

21:15 where the trade war is heading

25:13 why the US and Europe have failed to compete in manufacturing

27:13 the four-day vs five-day work week

29:26 Livio on tariffs

30:38 advice for businesses in a fractured world

36:30 where to find opportunities

38:04 generational businesses and succession planning

42:41 advice on starting a dream business

43:43 the relationship between service businesses and manufacturing businesses

46:45 climate change

Follow Livio Manzini on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/livio-manzini-2b8a5510/

Visit Bell Holding’s website: https://www.bellholding.com/en/index.html

Follow James Reed on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/chairmanjames/

James: [00:00:00] Welcome to All About Business with me, James Reed, the podcast that covers everything about business management and leadership. Every episode I sit down with different guests of bootstrap companies, masterminded investment models, or built a business empire. They're leaders in their field and they're here to give you top insights and actionable advice so that you can apply their ideas to your own career or business venture.

With Brexit and unexpected tariffs, throwing international trade into disarray, how can UK companies protect themselves during times of economic uncertainty? Joining me today on all about business is Livio. Manzini. Livio is the chairman and CEO. Of Turkish manufacturing company, bell Holdings, which has been in his family for three generations.

He's also president of the Italian Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Turkey. In this episode, we discussed the key to achieving success in manufacturing, what taking over a family business is really like and why we need to [00:01:00] ditch the Georgian calendar. Well today on all about business, I couldn't be more delighted than to welcome Livio Manzini, who's traveled all the way from Istanbul in Turkey to talk to us.

Full disclosure here, Livio is my business partner in Turkey and has been for 15 years now, and I've invited him to. Come and talk to us on the podcast all about business because every single meeting I've had with Li over those 15 years, I have learned something that I didn't expect or was interesting and I found helpful and I'm sure we're gonna learn a lot and he's gonna be sharing some new points that I don't even know about in this conversation.

Now Li is this CEO and Chairman of Bell Holdings, which is a manufacturing company based in Turkey, although he is of Italian heritage, he was born in Turkey. But is fluent in Italian and Turkish, and he's also the chairman, honorary honorary chairman, honorary chairman of the uh, Italian Chamber of Commerce.

In Istanbul and Turkey as well. [00:02:00] So thank you so much for making the journey Livio really warm. Welcome. I'm gonna ask you very self-serving question to begin with because I happen to know, because you told me before that your so early apprenticeship was served with a man called Philip De, who's a sort of legend in the recruitment world because Philippe founded its French and founded the company Echo in France.

Which later emerged with a company called ADIA to become Adecco, which was the ultimately the biggest recruitment company in the world. But your apprenticeship with Philippe was, I believe, here in the UK as he was expanding Echo in the uk. And I, I'd like you to just tell me a little bit about what you did and what you learned.

Livio: Well Jim, so thank you very much for having me here today. I'm must say it's a real pleasure and an honor to be in your podcast. Yes, the UK has figured prominently in my life different. Stages of my life. I was a student here. Then later I worked for a British company as their country manager in Turkey.

But, uh, Philippe Desto was my first employer after [00:03:00] school. And, uh, he was really charismatic, I think, I mean, shouldn't say this, but I think he was very good at, um, seeing the potential in people because I was very young. And the uk. The UK operation was not doing very well and there was even some question of whether it was going to continue or not.

So this was

James: the company Echo in the UK and

Livio: the company Echo in the uk it had 15 branches and that was basically fresh out of school. And they said, no, I think the people here deserve to be given a second chance. And he made me general manager, I mean age what? 24, 25. So, uh, I learned a lot. From him. So he put you in charge of those 15 officers.

It puts me in charge. Age 24, 25. Exactly. What did, and they saved the company, I think, but, so I shouldn't, you know. So you saved the company,

James: but what did you get from him in that process? You said you learned a lot from him. How did, how did he operate? What he, yes, I learned

Livio: a lot from him. Well, he had two.

Two ities. One, he was very cost conscious and he started with himself. So he hated costs. Hated costs. He [00:04:00] hated costs. I that hating costs. I

James: haven't heard that before, but, okay. Yeah.

Livio: In services, you, you really have to, to be very cost conscious. The margins we were making were clearly not very, very comfortable.

And therefore, uh, in his private life, he could be, you know, uh, it, it was said that the company was his wife, and his wife was his mistress. I. And could you explain that? So he was treating well, he was treating well, his wife. This is a continental thing. We don't have this sort of behavior in England.

Exactly. This is what they said in, in the company. And so, so he was extremely cost-conscious when I started, uh, going for him to the US it was always on. Uh, companies at the time existed like people Express or on, uh, uh, spare tickets that were sold at the last

James: minute. So not only did you not go business class,

Livio: no, no, no, no.

We didn't even go economically. We didn't even go economy. Super cheap, super cheap, super, uh, cost conscious. Also the hotels we were [00:05:00] staying in and so on. I remember he, he made you share a room with him, didn't he? Exactly, exactly. So to

James: save money, we once

Livio: went to New York and. We, we had to share the room 'cause the, they were very expensive.

So this was one of his popularities. But the other, the most important one, he was very charismatic, so people really loved to work for him, and he was very customer focused. And this is maybe the biggest lesson I took from him. I mean, he would not go to visit a branch, even a far flung place of France. At the time.

The company was mostly France without going to a customer visit. And branch managers knew if you, this was coming, they had to have a customer visit in, uh, in the program. And there were these books. And when somebody was visiting, they would make notes of, uh, sort of things to do. I. That were decided there.

At the time there were, there was no internet. There was no mail. And so next time you came, you opened the book and you said, oh, last time I was here, we talked about this. This happened in discussion. So [00:06:00] what happened? And you would follow up on that. Follow up, real follow up on that. You had really follow up.

So one was customer focus, second. It was, uh, also follow up. He was good at choosing his collaborators, his team, he had excellent people. And when he delegated, he basically delegated fully. I mean, at the time where communications, you know, we basically, I came of age when the facts started being used. So you couldn't micromanage.

I mean, I was in the uk, I was on my own. And I remember once I. Called him on a problem I had and he said, it's your battle. I know, I mean, it sounds IOUs than you saying, but I'm observing

James: that, and you're an in incredibly effective business leader. He was who he spotted when you were in your early twenties, so, but you saw that in others as well, that you worked Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah.

The people I worked with. Yeah.

Livio: There was also a kind of. Joy of living in, uh, in, in ako. People enjoyed themselves too. Yeah, I think that's, I mean, I mean they sometimes made fun of the [00:07:00] boss because he was stingy and so on, but,

James: well, people make fun of the boss. I mean, for some reason or other for some reason I'm certain.

Yeah. But they, uh,

Livio: they got that culture, so, you know, so there's nothing

James: wrong with being known for being stingy is so as you're trying to have a cost controlling culture, so there's some valuable lessons there. Yeah. So recently Livia, we, we were looking at our business plans for the year ahead for Reed Turkey, which.

We run together, her partners in, and we were talking on, on fairly dry subject of accounting and, and suddenly, you know, you shared with me a whole world of information I had no idea about, which I'm gonna ask you about now because I was so mesmerized by this. I felt it was absolutely fascinating. And this is about the way our calendar works.

I mean, I know you are biased because you're of Italian background, but in particular, why you think we should be using. The original Roman calendar, is that correct? Yes.

Livio: It's uh, it's a bit facetious of me to to say that we should move back to that,

James: but Well, let's hear it. I mean, it might be making very hearing said that it's essentially

Livio: pre Roman and [00:08:00] it, it is a.

A calendar, uh, or you know, the cycle of 12 months in a year, which is closer to nature. And we as human beings or as living beings have been programmed. Our metabolism has been programmed to work well in tune with the natural phases. As a matter of fact, the Economist, I think last week advocated for the elimination, uh, of, uh, summertime saying that it's, uh, you know, it's ridiculous to, to continue Summer.

I'm not more interested in

James: your arguments, Olivia and the Economist. No, but

Livio: what do you think, dear? Uh, coming back to the calendar, it's actually pre Roman with basically the year starting with spring. Spring year begins in spring, and life begins in spring. When? Exactly in the spring. Well, 21st of March.

James: So you're saying that's the spring equinox, that's the, that's the beginning of the year in the ancient, absolutely.

Livio: Today

James: in

Livio: Iran, which is together with the Vatican, the [00:09:00] only two ies I know, the biggest festival or occurrence in the year are not the Islamic ones, but the 21st of March. Nevro. The start of spring, and it is the start of the official year in today's Iranian calendar, and the whole country closes down for close to a week.

So this

James: predates Islam and Christianity, actionism of a cult of

Livio: fire and all that. And the Romans, of course, they started also with it and they gave names to the Mons. So it started with the odds of March, more or less, I guess. I dunno, what are the odds of March? Probably around 21st of March as So that's when it started, and this is why today a September, taking from the Latin S, which means seven should be the seventh month of the year and not the ninth.

Right month of the October, which is October 8th, should be the eighth, November. This must be particularly upsetting if you as

James: an Italian exactly

Livio: know all the numbers are like too out. Exactly how that

James: end up and more, and

Livio: it's, and it's not [00:10:00] working because September is the ninth. October is the 10th.

That's ridiculous.

James: Clearly. Yeah, exactly.

Livio: I mean, it's quite funny why that happened, isn't it? The Romans also messed it up a little bit. They messed it up. The Romans messed up. They messed it up. And then you have a Julius Caesar that comes along. Mm-hmm. And he decides that because he's, God, whatever, he has a.

All to himself. So he takes July. Oh, so he's so important. He gives the month his own name. Yeah. So ju in his own, July is the month of Julius Caesar and it has 31 days. Then, uh, along comes Augustus and he says, who am I? He's another

James: important emperor. Exactly. Yeah. So

Livio: he takes August to himself

James: and he can't have fewer days.

He cannot have fewer days. Oh. So he is got 31 as well. So

Livio: he goes that, where does he steal the day from? From the last month of the year, which is February he one.

James: Oh, I didn't know that. He steals

Livio: it from February. This is why February. Right. He's a bit of a, you know, bizarre month with less days than everybody else.

So

James: stole a day from February.

Livio: Well, yes. And then he had to, I be, he didn't know that he had to reschedule everything else because I didn't Yeah, so rescheduled it.

James: Yeah. So then what? So then February ended up [00:11:00] short.

Livio: February ended up short. And the numbers, the numbers are all out now, and it was the last month of the year and it is in tune with nature.

I mean, if you say that the, that life restarts every year in spring, which it does. And uh, our metabolism, everything else. I think also for business, I. It works better than the Gregorian calendar on top of it, obviously. Sorry. So just

James: explain the Gregorian calendar. Well, this is where we started 1st of January, what we have now.

Livio: And then of course the Russians have got something a bit different because the, the first Christian calendar moved to January and all that.

James: Yeah.

Livio: And then Pope Gregors, he also. Brought it back a few. He made some calculations and he changed this, so, oh yeah. The Orthodox and the Catholics have got different kinds of, there were riots

James: in England when the Poe did that.

Oh really? Because people thought they'd lost 10 days of their life. So it really kicked off in London. I remember studying that. So thats what happened. So there's a lot going on with these dates. So what are the implications

Livio: for

James: business?

Livio: Well, the implication of [00:12:00] business, I mean, right now we have at the end of year for companies that close down their accounts at the end of December.

Uh, which by the way, December, DHE 10 is the 10th, should be the 10th month, should be the 10th month, right? We have Christmas, which is a big holiday, then New Year, which is also, you know, time festival and we have to close the year. We have to make up our budgets, so it's quite stressful. If Christmas remained in December.

But New Year was either the end of February or the end of March. I think for business it would probably work better. Yeah, certainly for, so it could be the, for CEOs year, could for ceo certainly work Spring

James: Equinox would be your preference for that? My preference, yes. I think we might struggle persuade people to do that, but I, I would agree.

That's got a lot of appeal. The interesting thing, the nice time of year for a holiday as well. Exactly.

Livio: Interesting. Lydia, in, in some countries, the government's fiscal year is in March.

James: Yeah, it is here. Well, it starts, it is here. The, the tax year starts beginning of April. So your business, do you, does your accounting year end in December or another time?

Yes, it does. So ours used to, [00:13:00] and then we switched it to end in June, which I find quite helpful because it's, you don't have the stress of the sort of Christmas,

Livio: absolutely. No, no, you are quite right.

James: Activities.

Livio: Plus you divided the year, not in 12 months, but in 52 weeks, which is also brilliant. So just

James: to explain to.

Listeners. Our, in our business we have 13 four week periods. Exactly, yeah. Which we introduced, oh, a long time ago now, 2008, which was a bit of an adjustment from 12 months. But people like it 'cause they get paid 13 times.

Livio: Oh, okay. And I

James: like it because you get 13 goes at sort of making sales and, and then you can compare one period with another and the periods are the same length and so comparable rather than a 31 day.

Month Exactly. Versus a 28 day month, and that's actually the lunar cycle. So it's more in tune with nature as well.

Livio: Excellent. Yeah. Okay. So that, that's what

James: I like about it. Yeah. Sort of rhythm with the lunar cycle. What do you think about the clocks going backwards and forwards then, given this, 'cause that's an added piece of confusion that's been thrown in.

By administrators, you mean the summertime?

Livio: Yeah. Yeah. I think summertime is maybe at the time there was a reason. There is absolutely [00:14:00] no good reason for, I mean, the specialists say that it's not good for your health either. Well, because we all get jet

James: lag or something. Is it?

Livio: Well, I dunno. Well, in the spring I

James: find like this time of year, early summer, I wake up really early in the morning.

Yeah. 'cause it's daylight I suppose. And I like to get up early when it's like that, but I don't feel like that in December, which is now in my mind as the 10th month of the year. So I'm only gonna be confused. So. So this is interesting 'cause I think, well life works to certain rhythms, doesn't it? Exactly.

So trying to get your business business established in the way, our energy

Livio: level, I mean, it changes with age as well, but it does also change with, uh, with nature. And the idea is to get the most, to work in a company, to have the company work at its best. Yes. And the company is made up of people. Machines are important, but people are, as you know, always more important.

James: It's probably something that not many managers and business leaders give that much thought to, but it's well worth thinking about. You are based in Turkey, your businesses. Based in Turkey, could you just tell me a little bit about it? Bell Holdings?

Livio: Okay. Well, [00:15:00] bell Holding is turning 85 this year, so clearly I am, let's say third generation.

It was originally set up making soap, uh, so we didn't steal the name Bell from anybody. It was a, a soap. And interestingly enough, the brand belonged to Unilever. At the time, liver Brothers, port Sunlight was their main soap manufacturing place. It was 1940s. International trade has totally collapsed, and Turkey basically was not even producing soap.

Mm. So a, a group of European permanent residents, uh, in, uh, at the time, Constantinople, no, sorry, it was already Istanbul, maybe decided to, uh, to make, uh, soap. So they opened a small soap factory. And then if you fast forward to today, bell Holding is just a holding. And the companies that are fully controlled are all involved in making packaging material for fast moving.

Consumer goods plus some activities in services such as red Turkey, but the bulk is making consumer goods, packaging in both [00:16:00] aluminum and plastic for pharmaceuticals, personal care, home care, food. Those are the main areas. So what sort of

James: products specifically might you be? Packaging.

Livio: We make the packaging,

James: we don't fill them.

Okay. You don't fill them. The customer

Livio: fills them. Companies, I mean, multinationals such as Unilever.

James: So Unilever's still a big client.

Livio: Unilever is still one of our main customers. Yes. Yeah. Uh, we would make, for instance, Iole cans in aluminum for them. Uh, then for pharmaceutical companies, we make tubes for creams, ointments.

We would make bottles for ketchup, mayonnaise, or shampoo and so, so all

James: these things we sort of just pick up and use. Exactly. You probably take for granted. Absolutely. Yeah. You are producing and you do that and for Export Ally in Turkey, you Turkey cannot export

Livio: everything. Mm-hmm. But we do export and of obviously our customers in Turkey, they in turn, once they have filled the bottle or the tube, they do export the finish.

Right.

James: So a lot of these products, cans, bottles, end up in other countries. Exactly.

Livio: [00:17:00] Turkey is a, is a very good manufacturing hub, let's say, for these multinationals. Uh, some of whom by the way, are now Turkish multinationals because over time, uh, countries such as Turkey have developed their own champions,

James: right,

Livio: who have grown internationally.

James: I mean, Turkey, as you said, is a, is a very important hub for manufacturing now and seems to have won a lot of business from Europe and. Elsewhere, what? What is it about Turkey that makes it so good for this type of work?

Livio: After the collapse, let's say, of the Soviet Union? The first countries where manufacturing investment went were the Eastern European countries, places like Poland, Hungary, and so on.

Like in North America, the Americans developed this, what is being called the co prosperity sphere with Mexico, Canada. Us in, in Europe, we pulled in the ex, let's say Soviet colonies. Turkey was on the [00:18:00] fringes and then started becoming more important. What is in particular now that, uh, we want to say, just to use a term that is being used, decouple from China?

From the forest. If you look at it closely, there aren't so many other alternatives for the eu. Then Turkey. I mean, Turkey is a big land mass. So there is space to build, uh, greenfield sites. Uh, the infrastructure is excellent communications. I mean, Turkish Airlines is the airline in the world with the most international connections is number one.

Uh, telecommunications, uh, roads, shipping. You have harbors. You have. Top class, uh, harbors. You have top class banking system. You have people educated, good universities, big

James: population,

Livio: big population, and they are hard workers. I mean, basically at the end of the day, what makes a difference when I say is people, the Turkish worker is productive.

Yes, obviously the cost of labor is [00:19:00] still lower than in the U, but productivity is not just a question of money. I. Right. It's a question of flexibility of attitude to work. And, and in Turkey, all these are, are positives. I mean, we have factories outside of Turkey as well, and we see the difference.

James: So that positions Turkey pretty well for, I mean, how, how big is the population of Turkey?

Population of Turkey is

Livio: 85 million, right? Uh, it grew very fast. It's now like the rest of the world, uh, demographics are now. So it's not, uh, yet an aging. Country. It's just about there, it's starting to approach the threshold. So it might become more like Europe. It'll eventually, yeah, yeah. But it still has a catching up to do because per capita income is still lower than the EU average.

And, uh, the Turkey, the Turks are, are really interested in doing this, catching up. They want to get there. Isn't Turkey in the Customs Union? Is that correct? Exactly. One of the big advantages I failed to mention it, is that [00:20:00] it has a customs union with the eu. And now it has also, which

James: interesting, we, we do not have in

Livio: exactly

James: which, I mean it's quite

Livio: telling, but for the UK the relationship with Turkey is so important that the next day from Brexit, uh, the UK signed a trade deal with Turkey.

It was the first trade agreement they signed, and it was less than 24 hours after having was being left to you. And I didn't know that. Yeah, so, so that tells you that, and now they're negotiating an even deeper, let's say, trade relation between the UK and Turkey

James: trade is very much on the global agenda, isn't it?

Where the tariffs being increased and the potential for a trade war escalating. I mean, where do you think we're headed with all this? I mean, as someone who's been sort of involved all your career. Well, obviously

Livio: I, um, I view it with alarm, but also a lot of sadness because after, let's say the collapse of the Soviet Union and the failure of ideolog managed economies, let's say there was a [00:21:00] period, and they even said, you know, it's the end of history where everybody was in tune.

And the benefits of globalization, the benefits of managing economies rationally. And everybody was in agreement with that and it lifted billions of people out of poverty. Um,

James: so that's your perspective from Turkey. You could see that happen. Yeah. Yeah. You could see that happening. Yeah. 'cause I suppose in America, they all, in parts of the uk they saw certain cities and, and, and neighborhoods in decline.

Livio: No. There are always winners and losers. Yeah. That seems to be the case. And the politicians I think are at fault of not addressing, there are going to be losers and you have to address that fact. You cannot just ignore it.

James: So de-industrialization in Europe

Livio: and that sort of thing. Yeah, exactly. So, but it did the world a lot of good and the average American got much richer.

The average European got also richer, but not that much. Then at some point they stopped and now you have new walls being erected everywhere. Some of them, in my view, mental. And it is, uh, sad [00:22:00] because it's going to be, again, opportunities lost protectionism, hidden with the words. Fair trade has never actually created, uh, I mean some people will win clearly, but on aggregate I don't see that.

James: Well, the history of protectionism, I'm not an expert. You might be able to. Help me, but is that people have always decided they don't wanna do it anymore at some point. 'cause it hasn't worked, I think, or it hasn't given them the upside perhaps they were hoping for.

Livio: Well, you see, uh, we have this experience.

I mean, if I look at it from the point of view of bell holding, okay. Yeah. So our main company in 1980 was the company making aluminum tubes and aerosol cans. Turkey was extremely protectionist. It was a close society. Producer working, we could sell what we were producing at any price. People had no choice.

You wanted an YouTube or song, you had to come to us.

James: No one else was du So you supposed you had to market yourself.

Livio: You had to market yourself, and then overnight. The then Prime Minister [00:23:00] eliminated custom barriers.

James: So you went from high tariffs to no tariffs.

Livio: It wasn't just a question of tariffs. You needed import permits to import anything.

It was a fairly complex kind of, uh, thing to tell you. Uh, and it went on for much longer. The importation of alcohol was not forbidden. But it was the monopoly of the state and the state didn't use that monopoly. So no, alcohol was important, but officially it wasn't forbidden, you know? Okay. That kind of thing.

Yeah. So, and we had to adapt or die, and this is our motto, the motto of our company has always been adapt or die.

James: As your motto, you know, we had

Livio: the, I dunno how many people we had at the time, and now we have one third and we're making three times as much. It's more or less that kind of ratio because you become inefficient when you are costed and protected and so on, you have no incentive to become better.

You see? And, uh, this is why competition is, is so good. This is why, I mean, capitalism and liberal economics are based on this, but there are [00:24:00] losers. There are always going to be loses and tomorrow this could be us politicians have to address that. Many politicians,

James: not many politicians seem to be making the case for this, which is interesting.

Seems to have gone outta fashion or everyone's decided it wasn't the right thing. Exactly. But being back on the last 25 years and think that was a sort of golden era, being a liberal. Today in the US I think

Livio: is an insult.

James: I don't think it is here, but there is a liberal party which doesn't get a lot of votes.

No,

Livio: no. I'm not talking in terms of, uh, no, I know. Member of the party. It's become,

James: it's become sort of a label that find disparaging. So flipping it from the Turkish experience, why, why do you think the US or Europe has not competed successfully in manufacturing? Why, why is it that we, you know, 'cause this is where manufacturing started.

Livio: Yes. It's still continuing, you

James: know? Yeah. But it doesn't seem continue. I mean, not

Livio: in the UK that much, but Germany and Italy are still big, uh, manufacturing, uh, countries and manufacturing is still an important part of their economy. And now Spain as well. And then [00:25:00] as I told you, Poland and Hungary have taken, uh, have taken over.

But at the end of the day, it's really about, first of all, clearly innovation. And secondly about, uh, productivity. I'll give you a very simple example. If you work five days a week and another country, the blue collar workers work six days a week. Like in Turkey, I. Okay, so that already is a, uh, 20% difference.

Okay.

James: Oh, you didn't say that earlier. So the Turkish worker works six days a week. Six days a week, yeah. 48 hours. 48 hours, exactly.

Livio: The difference between five and six days is not just a question of labor work time. Your capital invested in the machinery is also working only five and not six days.

James: Yeah.

Livio: So the price at which you have to sell the goods that come out, you are losing out on the economies of scale because you also now have idle plant.

In a world where everybody's [00:26:00] working five days, uh, a week and all the plans are closed for two days, that wouldn't be so dramatic. But it's not the case, and it's not just a question of how much you pay the workers. I haven't done the maths, but I think in Europe you could pay people more but get them to work more.

Now we seem to be wanting to work less for more. Uh, clearly life work balance is important, but, uh, at the end of the day, when you are in production processes, which are continuous, you need to keep plant and machinery working all the time.

James: So there's a debate, or in the UK some people are arguing for a four day working week.

Do you have that in Turkey or people advocating that? No, no, no. You're looking at bit incredulous and I think the people who are making that argument, uh uh, don't expect to get. 80% of the pay, they expect to get the full pay for the four days. And the, the idea is you do 10 hours a day for four days instead of eight hours a day for five.

What would you take on that? Well, it, [00:27:00]

Livio: it really depends what kind of business you are in. But for manufacturing that. Doesn't work. Are your manufacturing plants open

James: 24 7 or? Yes, absolutely. So you are running all the time. Yeah. Yeah. And shift difficult. So you just have to schedule people to always someone shift

Livio: work.

You do three times eight shift work is, is difficult. I mean, we talk about being in tune with nature. Yes. Clearly working at night is not natural and therefore people work at night do get more. It's, it's all fair, but you need to keep the plants working.

James: I hadn't thought of that. If you have. 10 hour working days, you can't get three in a 24 hour.

It's very difficult. That's why that's goes with what you were saying right at the beginning. Yeah. Eight hours work, you have to build

Livio: a fourth shift or a fifth shift. It

James: becomes very, and people don't get enough hours. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I suppose that's being sort of driven by people who work in service type.

Livio: Well, exactly as I'm saying you, it depends the type of business that you're in.

James: Well, the message I'm receiving from you is we are in a very competitive world. And if, if not, [00:28:00] everyone's working at the same pace and at the same, on the same timetable, don't be upset if you get out competed.

Livio: Well, I mean the Chinese have got two advantages.

They work very hard right now, by the way, their monthly salary is, has gone up. Chinese, you know, the Chinese, they're not working for a pitance. So quite well paid now, well, quite well. They're much better paid than, than the time. I mean, I think it's coming close to Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, whatever kind of side.

But they work the hours. And they're very productive. They work very hard and they have a scale. Yes. So they have these economies of scale, which are very difficult to match because they're, you know, they're producing for an economy of 1.3 billion people.

James: What do you think will happen then with these tariffs on Chinese goods?

Livio: No, the tariffs are, I respect everybody's opinion. I don't see any good. Coming from the tariffs. And it is actually surprising because the economy of the US was really at the end of the Biden area in great [00:29:00] shape and it was top dog in the world. Uh, when you look at the per capita income between the US and the eu.

Like 20 years ago it was fairly close and then it diverged and the US is now much richer. So criticizing on Paper U seems, seems very strange,

James: but it is on paper, isn't it? Uh, but is that money evenly spread, you know, the per cap or income, or is it all gone to people like Jeff Bezos who's sort of worth a fortune?

Yeah,

Livio: no, no, that's, that's a good point. I don't, I don't know. I mean, clearly inequalities are much higher. In the US than there would be in some, uh,

James: EU countries. Clearly. And this now global sort of change is driven by US politics, obviously. Absolutely. Yeah. Yeah. 'cause the president is, seems to be doing absolutely what he said he'd do when he sought election.

I. He is giving his voters what they asked for. Isn. Oh yeah, yeah, absolutely. Yeah. So that's sort of, so not much the rest of us. So we've gotta live in this world of sort of fractured trade. Well, what advice would you give to businesses?

Livio: I mean, [00:30:00] the businesses, your experience in the eu, let's say, or UK or even the American ones.

You have to always be one step ahead, and that is r and d innovation. So investing in, uh, higher education, uh, research. Automation. I mean, one way to reshore some jobs is to make them highly automate. We ourselves are very much involved in trying to improve our productivity with digitalizing our production lines, and after that, trying to automate them.

But for. Uh, European UK business, it's a life or death situation. I mean, you need to stay one step ahead in a sense.

James: You say that extreme. Why do you say that life or death situation, that's a strong

Livio: Well, because if you're going to compete with the productivity of your labor force, it's going to be difficult because you're not going to go back to a six day week.

So you need to do more with less. And this is automation. Highly automated, uh, factories bringing in robots. A lot has [00:31:00] been done. A lot more can be do, can be done. And I think the public authorities, the governments have to pay for. Part of, of this transition, let's say what is in a sense of swearing is that the Chinese are doing a lot of that.

So against the other emerging markets like Brazil, South Africa, India, whatever, uh, we can still stay one step ahead with China is more difficult.

James: So this might be a trade war that China wins. Ooh,

Livio: not up to me. Speculate. No, not up to me. Escape. I tend to believe that trade war losers.

James: Yeah. They're only losers.

Yeah, there are. I can, at least this is what I think. I can see why you would say that. Let's talk for a little bit about sort of business through the generations. You, you said your company's 85 this year. Our company is 65 this year. So you've got 20 years or less. Congratulations. Congratulations to you.

So your third generation, what's it take for a business to transition and grow and be, you know, super relevant like yours through three [00:32:00] generations? And, and what are your thoughts for the future?

Livio: Uh, it's adaptability. Being agile, adaptive, and open to new ideas. In our case, you know, we moved from making soap to then making packaging.

Then we were in a protected environment. The Prime Minister at the time, in 1980, he opened up the country all of a sudden, and in our company at the time, it was headed by my father. They didn't sort of whine or cry or whatever. They said, okay guys, you know, let's get. Don't to work, we have to remain relevant.

So we have to adapt, we have to be agile. Uh, what did they do at that time to Oh, invest, invest in, uh, more, uh, in better plant and machinery. So they put more money into the business? Exactly, because it was, at the end of the day, when you are in a protected environment, why? Invest in your machinery.

James: You can run your old

Livio: ones from as long as possible.

Yeah. Until they die. Then you benchmark. That's the other thing. You have to be extremely fair with yourself and call is spade is spade. You have to know where you are. You [00:33:00] have to benchmark yourself with your competitors and see the distance. And the distance can be a matter of despair or can be a challenge.

Okay. This is our target. But

James: you're saying you, we can do, you were behind the competitors when you started. Yeah. International competitors. Yeah. Oh yeah. And that was quite hard at the time, I suppose that Yeah. But they did it. And then when I came, just a question. How, how did you do that at benchmarking excerpt?

Do you get consultants to do it or your own people? Yes. You get, you got some outside help you get consultants. Yeah. International. And that's what you asked for a benchmarking ext.

Livio: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. You can also, I mean, we joined international associations of companies doing the same job, and we do have benchmarks internally,

James: but you suddenly became quite outward looking.

I mean, you really embraced the change rather than complain

Livio: about you embrace the change. Uh, but in order to do that, you also need, and that's also where, you know, maybe a bit like this to say we had in the company people that were you, you cannot impose that. You can, uh, preach by example, but they have to be.

To have an open mind, [00:34:00] uh, because you will hear like, oh yeah, this worked elsewhere, but. This is Turkey, or we've been doing it quite successfully like this for many years. Why change? In our case, it, it wasn't, it wasn't like that, first of all, maybe because they, they thought, okay, we, we can be hammered here.

So that worked quite well and when I came along, I came with a different set of experience. So this, I would also recommend, I mean, tool for me doesn't necessarily work for everybody, but I had. 10 years work experience, I mean, with Philipp Dezi, and then I joined Glaxo with Glaxo. And so, so I was bringing my own credibility in a sense.

Mm-hmm. And again, when I brought new ideas at the time when, uh, Turkey was continuing to open itself up to the world within the company, it was seen as an opportunity, not, uh, as a risk. So that was quite good. And I must say at the time, in most of these countries, which. It ended up to open up more or less in the [00:35:00] nineties.

You know, it was fairly easy to start something and be successful because you could just, you, you just needed to look what had been successful in the us, what had been successful in Europe, and it was a globalizing world. So I thought, you know, chances are it's going to work here. This is how I brought temporary stuff and some which didn't exist.

Uh, I also introduced guarding services. You know, uniform didn't exist. So these things worked clearly. I may have missed some opportunities. Some of the biggest successes have been in mobile telephony. I erroneously assumed that the big winners in mobile telephony would be the legacy carriers. I. But it didn't work out that way.

So you could, you could

James: have set your own one up. We will have regrets like that. Well, maybe, maybe not. What do you think about now though? What? What would you see as, do you still look for opportunities from the US or Europe now and what would you be looking at? Well, we

Livio: still do, but it's harder now because everything moves so fast.

Technology, [00:36:00] uh, communications and. There are startups everywhere. I mean, Turkey also has its own startup base.

James: Yeah. Information's much more available now, isn't it? Much more a, you can see what people are doing. So,

Livio: so you need, in a sense, instead of bringing something in, we are now at an age where you need to have your own idea.

You need to spot an opportunity, you need to invent something yourself. It can be a service. Doesn't have to be,

James: yeah. So how would, how would you, would you be looking to reinvent? Bell in this. It's a head to a hundred. Spotting.

Livio: Spotting.

James: Have you got anything in mind though?

Livio: One thing that I learned from some of our customers is that there are still what is called.

White areas in, uh, in the world and also in packaging. So there are some countries which are big countries population-wise, but have not yet, let's say, are just potential. Africa is considered, you know, one of them. Yeah. Of those areas, and therefore there could be opportunities, uh, in these. But would you go and establish

James: that potentially.

So you, why not? You should open a factory. Yeah. Okay. Do you have factories in Africa now?

Livio: No,

James: [00:37:00] no, no,

Livio: no. We're present in Bulgaria and in Italy. Yeah. With a, with a factory.

James: So you could go and expand. Exactly. I mean it obvious,

Livio: eh, is a huge country. A hundred million people. It is. And very little manufacturing base.

And those people also need the same shampoos or the

James: orant. Yeah, they certainly do. And it's a, it's a very interesting country. I've been fortunate enough to visit it. Oh, good. Okay. I could recommend you go and have a look. So what about the sort of movement from one generation to the next? What are your thoughts on that?

Are you gonna continue as a family business, do

Livio: you Well, exactly. I, um, I always consider that, um, I took it in trust for the next generation when I took over from my father. And so yes, I want to give a chance to my children and my eldest son is working in one of our.

James: So he's interested in, so he's interested.

So he's, he's your sort of a lightly successor.

Livio: We have three children, so. Right. I want to give them a chance to, uh, to take over if they want to, but he cannot be forced. My father never forced me to come [00:38:00] back. No. It was my decision.

James: What, what did he do to lure you back?

Livio: Well.

James: Because it's not, not against the next generation company came

Livio: back, I came back as I was, uh, recruited by Glaxo Pharmaceuticals to be general manager in Turkey.

Obviously I was looking for a way back. My father helped with introduction, but then I came to Turkey's general manager of Glaxo, and I had the possibility to have an international career in Glaxo. So after Turkey go somewhere else. And at some point I, I decided, uh, with, of course, I. The approval of my wife to make the jump and quit an international career for joining the family firm.

I have no regrets.

James: No regrets. That was gonna be my next question. No regrets. So that was a good decision. What, so what? What? Glaxo was a fantastic company. Sure. It is a fantastic, it was a F. So you made that decision. Why are you so comfortable with it? Why do you have no regrets? Why do you think it was a good decision?

What is it about running your own business that you particularly love? Well,

Livio: I have always been an entrepreneur at [00:39:00] heart, so I always wanted to build. Companies, basically. Yeah. You have it in your, I have it in my blood. I think, um, called a serial entrepreneur and obviously, uh, the family company was, uh, was the right place where to do that.

I mean, when I joined the family firm, you couldn't

James: have done that at blacksmith per se. You'd have to convince a lot of people to start something new there. Exactly.

Livio: When they. Joined a family firm. I initially spent very little time, uh, looking at what was happening already. I did my own things and Okay.

Most of them worked. Most of them.

James: You're ahead of me then. So, so I think, I think one of the things that my father said to me, you've reminded me of it. It's that, you know, a business is a vehicle and you think of it as a vehicle, you can take it in any number of directions. You don't have to keep doing what we're doing now.

No. And and you've illustrated that saying, you know, you started out in the soap business and now you're doing all sorts of different things. Exactly. And you've built a, a successful business by starting and trying new things and looking for what. The market [00:40:00]

Livio: wants, I

James: guess.

Livio: But

James: you,

Livio: as they say, very often, no enterprise is built on dreams.

None without, you have to, of course, have a vision. You also have to have, uh, I haven't heard that saying before. Your feet on the, so, so no enterprise

James: is built on dreams, but none without, exactly.

Livio: You hadn't heard that?

James: No, I didn't invent it, so, oh, I, well, I, I like it. And so let's explore that a bit. So what does that mean to you?

Livio: Well, it means to me, you see, sometimes I have young people, let's say, that come for advice and some, you know, look at my past and say, yeah, I would like to be my own boss. I would like to have my own company and build my own company. And I tell them, okay, do you have a dream? Having your own company is the result of the dream.

You don't start by building a company and then deciding what to do. You need to have something in your mind. You need to have spotted something, uh, that you're making, going to make a different hamburger or because you see that the current ones are not good enough. I'm just, you know. Yeah.

James: Picking that as an example.

Yeah,

Livio: just picking that as an example. So something you

James: care about or

Livio: something you care about and you see an opportunity and [00:41:00] you say, you know, I'm not satisfied. I think I can do better. And then you start selling this idea to friends and family. And it's like, uh, you get in love with your idea and building the company is the next step, maybe, maybe in your garage or whatever, but you have to start with the idea, with the dream, with the, and, and very often money is not involved.

I mean, you don't set it up because you want to become rich. If you're successful, then you make money and making money becomes the measure of the success, but you don't set up. To become rich. You set up to make a better hamburger. Yeah. You set up to make a better sock

James: or whatever. Yeah. I think that's really important advice to all would be entrepreneurs because you know, solving problems is what Exactly.

Yeah. So often about. Is there anything, you said you, you, you born entrepreneur. Is there any advice you'd give to people who have shared that feeling? Who want to get started? I, you, you, you've said you have a dream, but what are the [00:42:00] practicalities? Well, the

Livio: practicalities is unfortunate in the, the rest is, is pain.

It's a lot of pain. Pain, pain is so, be,

James: prepare for some

Livio: pain. Well, what, which means, what pain are you talking about here? Well, it's 24 7. When you get on on an idea, forget about sitting in your office and directing other people. You have to be on the front line, day in, day out. That has not changed. So that's the first thing.

And the second is that, unfortunately, sometimes it doesn't work. So you have to give yourself a stop-loss.

James: So you have to, yeah, that's hard to do, isn't it? It's very hard to do. Build an idea that you've put so much passion and energy, but you have

Livio: to be objective enough with yourself to see. Whether, you know, it's not working out, maybe it was too early.

Do you get someone else to help you with that or is it just that Yes, it would be good to have somebody help you with that. Having a virtual boards and there are associations that do that. Mentor or something. Yeah, mentor. There are associations that do that too.

James: Yeah. 'cause otherwise, you know, you can keep going, doing the [00:43:00] same thing for far too long and yeah.

You run services. I mean, I, I'd like to explore this as we come to a close, but you run service businesses and manufacturing businesses. What have you learned from the sort of overlay, because often people are in one or the other, but you are pretty unique in doing both. Yes. Welcome one section one, but I know how unique it

Livio: is, but in my case I see a lot of overlaps and that's strange to to say.

First of all, let me clarify something. We are in manufacturing, but we make to order. So all our customers are asking tailored jobs from us. We don't produce for stock, put it in shops, and wait for people to come and buy it's orders because it's intermediary goods. So say Unilever needs aerosol cans, they place an order.

We make it the shape they want. They may, we make it, uh, with the print they want, et cetera, and it cannot be sold to somebody else. I'm saying this because in both cases, the service part of the offering [00:44:00] is perhaps in some cases even more important than the quality. Because you need to be attentive to the needs of your customer.

Every customer is different. Every customer has different requirements, different needs, and a different culture. A different approach requires a different level of attention or detail, like in services. And this is what makes you or us successful. Uh, we have, we're pretty proud that we have developed a longstanding.

Relationships with their customer that go back to, well, in the case of Unilever, 80 years, but, um, with others pretty long time. Uh, not because they didn't have an alternative, but because if you are giving them what they want in terms of quality, but also service and you live the journey with them, they don't necessarily need.

To go and look for something else. Uh, and that's separate. I mean, we've lost customers and we're making, gaining new ones. Very often we gain new ones because they're not happy, not with the [00:45:00] quality, but sometimes with the service that they're getting from, from competitors. So the service element becomes so important that service companies manufacturing have got.

In that, so I see in a way you, it is an

James: overlap there brought sort of a lot of service expertise to manufacturing and some, have you also brought manufacturing expertise into services? I, I try. I try. Well, yeah. I, I associate really slick. I try slick manufacturing with great automation and Exactly, yeah.

Efficiency, just in time inventory, lack of waste. You try?

Livio: Yes, I try. Is

James: it more difficult to do that in services? It's

Livio: more difficult to get service productivity up than machine productivity up. That's interesting.

James: It's also difficult to get consistency, isn't it? Because of Oh yeah. I suppose because of the involvement people.

Exactly. Yeah. You can produce a widget over and over. Absolutely. And it comes out pretty much the same. Absolutely. But the service delivery, I mean that's, I suppose McDonald's is an exemplar of sort of producing something consistently all around the world and you know what you're gonna get when you walk in.

But there are many examples of that.

Livio: [00:46:00] Absolutely. And there are. They are very careful about that.

James: Yeah. Just to wrap up, I mean, obviously climate change is a huge concern for people around the world. You are in manufacturing, there's a lot of policy around net zero that seems to be coming up against pushback because people say that it's increasing energy costs and it's making it impossible for.

Companies to produce things a price competitive way. Where do you think we're going with this and what do you think should happen next?

Livio: It's both a good question, and I don't necessarily have an answer. I, I, I think climate change and global warming is the biggest threat that, uh, we are facing and we are, I think, past the level we can keep.

Global temperatures below this famous 1.5 degree. We have to look at ways to minimize the impact instead of preventing it to adapt again, adapting, and therefore it's, we are in uncharted territory and US administration is going in a totally opposite direction, [00:47:00] not caring too much about it. So it's not going to make it any, any simpler.

The planet will survive, planet will change, but it'll survive. What we're talking is about the survival of. Life of human beings and some parts of the planet will become inhospitable. And so there are going to be massive movements of populations, probably. And then we're talking of course about the animal species in the seas and so on, who are also, you know, threatened.

We now see tropical fish in the Mediterranean and they are, uh, seem much more aggressive and they kill off the, the local ones. As I said, the planet will survive. Yeah. How are we going to live on this planet? That is, uh, that it is what we're talking about. We are also more and more people. The standard of living of people have is increased, so the consumption of consumer products, packaged goods, success increase.

So we produce more and more. Trash or post consuming. Mm. And therefore we also need to address that problem. We are [00:48:00] running out of space for landfill, so we have to go past landfill and we shouldn't be throwing it in nature or in the seas, even though according to me, deep sea fishing, there's much more harm.

To the ocean population, uh, fish population, the ocean, then, um, than plastics, but it has to be addressed. We are trying to do our own little bit. We are starting a recycling, uh, business for plastic packaging, but governments have to be more involved. I mean, it's a question of fiscal policy and it has to be what,

James: when you say fiscal policy, what do you think they should do?

Livio: Well, I mean, if you want to. People to use more recycled plastic material. You have to make the virgin plastic material more expensive. People react to that kind of stimulus. If you say you have to use 30% in your packaging, that is an empty threat. Yeah. But if you have to pay more. Or when you buy plastic, when you that you have a tax on plastic, uh, virgin plastic, then you make recycled plastic more.

James: Has anyone done that? Has anyone introduced that?

Livio: Yeah, apparently they should. [00:49:00] But you cannot introduce it just in the UK then you make the uk No, that's why I was wondering. 'cause it makes and competitive, that's a concern. It has to be coordinated.

James: But that hasn't happened. Yeah, no,

Livio: that is not already happening.

James: So this question of coordination has come up more than once.

Livio: Yeah. You cannot rely on the consumer. I mean, the consumer, uh, will not pay necessarily more. I mean, some will, but it'll

James: not be

Livio: a

James: mass movement. But then I suppose governments are reluctant to make things more expensive for people Exactly. When they're already struggling with the cost of living crisis.

Exactly. So we called this Exactly. Yeah. That's the whole point. That's the whole point. So maybe it's innovation we need to rely on here.

Livio: Yes. There are, uh, lots of, there is a lot of research. Yeah. Everything

James: became biodegradable.

Livio: Yeah. Enzymes.

James: Yeah. That'd be very good. There is a lot

Livio: of research in that.

Absolutely. Likely that something you see a

James: future in which we might have totally biodegradable packaging,

Livio: totally biodegradable or, uh, enzymes and other, let's say processes to degrade the plastic. Even if it wasn't by, okay. Yeah, yeah, yeah. There, there is a lot [00:50:00] of, uh, that's research in that space. Well that's because I mean,

James: there's a lot of garbage around and it would be good if it was Yeah.

Recycled dump and uh, you know,

Livio: loading it into a ship and sending it to the other end of the world is not a s slosh.

James: No, no. They have rubbish dump somewhere else. That's what happens a lot, doesn't it? Yeah. So offshoring of carbon and. Rubbish. It's not a solution. Not okay. Olivia. Well, thank you very much for coming and talk to me from Istanbul.

I think that's, we've covered a lot of ground there. I found it fascinating. I'm going to go back to a Roman calendar by myself and see, see why. Let's do it together. Let's do it together. I think business should take the lead, I think makes a lot of sense. But I think trying to work in harmony with nature and the natural world makes complete sense to me in terms of people's wellbeing and energy and that of our organizations as well.

Now I'm gonna ask you, I ask you at the end, two questions I ask everybody. Okay? And the first question is in, uh, is a clue on the wall here, what is it [00:51:00] that gets you up on a Monday morning, Livia?

Livio: Well, today's a Monday. So this morning it was your podcast, basically. Fantastic. Looking for it to your podcast.

James: So I certainly that got you posted.

Livio: Made sure I was awake before seven this morning. Good. But, um, uh, apart from that is I'm always connected, so I never really switch off. So the weekend is when I start having, you know, sometimes weird ideas, but ideas and so on. And so I look forward to Monday because.

That's the moment when I can, uh, get my collaborators around me and bounce off the wall. Say, okay, see what, make your weekend's ideas. Exactly how can we do with this? Yeah. You know? Uh, so I look forward to Mondays. Yes. Yeah. I do love Mondays.

James: Oh, I'm pleased to hear that. And I like the idea of weekends being a sort of time for.

Gestation of ideas. And then my last question, which is in it, it's in the Italian version of my interview, but why you, which is behind you there? Olivia, uh, as well as the English one is one of the [00:52:00] fateful 15 interview questions. It's where do you see yourself in five years time?

Livio: In my case, it's fairly obvious, let's say, because I've told everybody that I want to retire from.

Uh, day-to-day operations when I turn 70 and I'm 64, so, you know. Okay. The company will have turned 90 by then, so really my challenge is succeeding in the succession planning and then being more of a mentor and, uh, okay. I may have some personal projects. So you, you

James: wouldn't be chairman or I

Livio: could be

James: non-executive chairman.

Right. But you want to step back at 70? Yes, exactly. I wish you total success with that Livio. Thanks very much. But not to stay home and watch tv. So I suspect you won't be doing that. That's good to hear. Thanks Livia. That was really interesting. Thank

Livio: you, James. So did you

James: learn something? Yeah, I did. Adapt or die.

I like that. Oh, thanks again for coming in. It's lovely to, to see.

Livio: Thank you James. Much appreciated.

James: Thank you Livio for joining me on all about business. I'm [00:53:00] your host, James Reed, chairman and CEO of Reed, a family run recruitment and philanthropy company. If you'd like to find out more about Reed Livio and Bell Holdings, all links are in the show notes.

See you next time.

All About Business is brought to you by Reed Global. Learn more at: https://www.reed.com

This podcast was co-produced by Reed Global and Flamingo Media. If you’d like to create a chart-topping podcast to elevate your brand, visit Flamingo-media.co.uk